Blog archive

10 September 2011 to 12 January 2011

Web site interruption

As part of the annual rejig and forthcoming blog changes this web site will possibly disappear briefly some time over the next week or so. The interruption should be very brief and I’ll try to keep the site available via www.bemuso.co.uk when this URL is off the air. If everything goes pear-shaped it might be longer but I have a plan now, so what can go wrong?

New year, new plans

My web site here is becoming cramped and underpowered—blogging in HTML has really brought this home, with no RSS feed, social feeds or blog comments (among other things). So I’ve been quiet lately, reading up the possibilities.

If I was starting from scratch it would be simple but I want to migrate without completely re-working search, inward links and the structure of the content. Eventually I’ll move the hosting and revamp the whole site but in the mean time I think I’ll replace the landing page with a Wordpress blog. That will bring me into the 21st century without too much upheaval and I can then plan a longer term solution and research fully hosted options with more presentation tools.

I have several blog posts in the pipeline, so for now I’ll wish you all a happy new year and get back to testing Wordpress.

The strange plight of web copyright

I’ve watched government Internet regulation since the USA Digital Millennium Copyright Act (DMCA, 1998). The Consumer Broadband and Digital Television Promotion Act (CBDTPA, 2002) proposals which followed—and failed—were insane. Over here we have our original Copyright Designs and Patents Act (CDPA, 1988) modified by the the EU Copyright Directive (EUCD, 2001) and our subsequent Digital Economy Act (DEA, 2010) rushed through by the dying Labour administration.

The USA is at it again. Combating Online Infringement and Counterfeits Act (COICA, 2010) didn’t pass into law but has returned as Stop Online Piracy Act (SOPA, 2011) and Preventing Real Online Threats to Economic Creativity and Theft of Intellectual Property Act (Protect-IP, 2011). You may have seen some of this debate online.

Cameron, the UK Prime Minister, has set up the Hargreaves Review (a rehash of the previous government’s Gowers Review) to modernise UK copyright online. He believes—mistakenly in my view—that copyright must be more flexible to support Internet entrepreneurs (in his words, like Google).

It’s one of those debates that has become polarised into right and wrong. If you criticise DEA and SOPA you must be a freetard if you don’t you must be a dinosaur. Unfortunately, that sums up 99.9% of the whole discussion. Of course, nothing is that simple. These regulations involve many complex issues: the role of ISPs, copyright registration, license databases, orphan works and collective licensing among many others, as well as the technology that goes with them.

The big problem is governments don’t understand the Internet. Even the best-informed seem to think it must be easy to “clamp down on piracy”. It isn’t. They don’t even have a good grasp of copyright. Well, it’s not easy.

Big Business lobbyists are no better. Major record labels have long confused file-sharing with “piracy”. Every download which doesn’t pass through their cash register is theft.

Internet Utopians don’t help. They would be quite happy if rights were swept aside so that information could finally be free.

It’s a mess.

What’s the problem? We had a (kind of) working copyright law. Have things really got so bad that we need all this mayhem?

I don’t think so.

Some changes are needed but the basis of copyright—that the creator owns their work, for a time, without asking—must stay. And the interests of Big Business are not so threatened that they must be given control of what gets published on the Internet.

The DMCA safe harbour which allows Grooveshark and YouTube to host infringing material is not working. The complex licensing system which charges users and rewards owners has become distorted, and territorial licensing is somewhat daft in the age of the world wide web.

In recent years PRS has recognised the growth of individual rights owners by lowering its membership fees and distributing income at small venues directly to the performing songwriters and composers who earn it. By contrast, government copyright drafting and legislation remains dominated by Big Business and large copyright owners—the Major record labels and publishers.

The history of copyright, since 1709, is patchy. Vested interests have frequently abused their power. Lobbyists from all sides are once again making all the noise but copyright is important for everyone. Joe Bloggs’ cat videos can earn more than a big label pop record and small artist Facebook pages should not be threatened by spurious takedowns. Let’s hope government is listening to their people as much as the lobbyists, and if you have an opinion let them know.

Who owns the artists?

This will be an interesting case This Is War: MegaUpload Now Suing UMG Over DMCA Abuse...

The media tend to side with MegaUpload on the basis of artist approval, or with UMG on the lack of it, but Major label artist contracts are normally exclusive regardless of the wishes of the artist. It’s entirely possible UMG does own copyrights in the MegaUpload song even if all the artists gave their consent. Without specific releases from UMG the artists’ consent is not enough.

Billboard reports

“Let us be clear: Nothing in our song or the video belongs to Universal Music Group. We have signed agreements with all artists endorsing MegaUpload,” MegaUpload CEO David Robb told TorrentFreak. “Regrettably, we are being attacked and labeled as a ‘rogue operator’ by organizations like the RIAA and the MPAA.” … “UMG didn’t do proper due diligence before sending the takedown notice… And each of the other artists, including Will.I.Am, signed a broad written agreement allowing the use of their likeness and their statements in the context of the video.”

Statements are probably OK, but some likenesses and musical works are probably assigned exclusively to UMG.

It seems fairly unlikely to me that MegaUpload has examined 1,800 or more pages of big label contracts to see if they can make this record. The chances of getting it wrong are high. On the other hand they may understand that perfectly well and think the benefit of the PR outweighs the possible legal costs.

Update: Friday 16 December 2011

The debate continues. This BoingBoing post claims:

…Universal has some sort of special deal to arbitrarily remove stuff it doesn’t like from YouTube, even if that stuff is legal.

Words almost fail me. I’m no fan of UMG or the Major labels but it’s obvious a commercial contract between UMG and YouTube has conditions. Their contract won’t be limited to excluding illegal uploads. The normal Major artist contract is over 100 pages, today’s 360° lockdowns make it unlikely the artists themselves have any say in the matter.

This CMU report of the same press release manages to apply more thought and less hysteria to the news.

Of course, MegaUpload has got the publicity it wanted and public sympathy was never going to be with the biggest record company on Earth. But many journalists and bloggers covering this story, having first decided which side they are on, have leapt to predictable conclusions. Without access to the contract details and some expensive lawyers it’s impossible to guess what the judge might say.

Update 2: Friday 16 December 2011

Well, it looks like BoingBoing was right after all. Apparently UMG offered no defence and the video is back up. UMG out-lawyered, who’d have thought it?

Update 3: Sunday 18 December 2011

YouTube have denied there is any contractual takedown agreement with any of their partners, including the big labels.

Our partners do not have the right to take down videos from YT unless they own the rights to them or they are live performances controlled through exclusive agreements with their artists, which is why we reinstated it.

It’s hard to tell if this story is finished and if we’ve seen the full truth yet, it seems likely we haven’t. But we have learned some intriguing things about UMG. Although they contest the legality of cyber-locker (cloud account) music sites like MegaUpload UMG seem to have no way of dealing with them. And although UMG’s entire business is based on exclusive 360° contracts with their artist roster MegaUpload was able to make a promotional video using UMG artists (among others) and post it on YouTube. Finally, for now, UMG used the YouTube Content Management System to block this video in the knowledge it would be overturned by a court. That seems pretty desperate.

Access v. Ownership

Here’s an interesting blog from Mark Mulligan Why The Access Versus Ownership Debate Isn’t Going to Resolve Itself Anytime Soon a couple of days ago. I agree his general argument but I think the case for ownership may be even stronger than he suggests.

Ever since they buried Napster the record industry has tried to breathe life into the rental model. This is what they always hoped the Internet would give them. Pundits have talked about the inevitability of streaming services for over a decade, ignoring the evidence of iTunes. The current Spotify campaign is just the latest example.

Where I differ from Mark Mulligan (and Spotify et al) is those bottom two aspects: Play Everything and Share With Everyone. His illustration gives these points conclusively to the access model. But is that true?

When will we be able to “play everything” through Spotify or any other streaming service? I have written before about the myth of everything everywhere. No streaming service offers everything in my record collection, let alone everything in the charts. The Majors’ cold feet over On Air, On Sale is just another fly in the ointment.

And when will we be able to Share With Everyone on Spotify (or anything similar)? Spotify has 10 million users and many people I know aren’t there, or on Facebook, or any of the other media darlings. The glaring problem here is walled gardens: Spotify users can’t share everyone’s playlists, even with the new apps. This is what the pundits call content resolution. The log-ins that protect different services stop them being open and useful.

People don’t really need “everything”, they just need what they want. For me Spotify comes up short but my record collection is complete, and when I want something new I simply add it. It won’t always be on Spotify, so I give that point to ownership.

And people never really want to “share with everyone”, they just want to share. Spotify can share on Facebook but not to people who aren’t there or to Friends who turn off share-bots. Is there a real sharing problem for people who aren’t on a streaming music service? We have YouTube, email, web sites, blogs and all the walled-gardens. Streaming services have a way to go before they can equal the web at large, when it comes to sharing.

The Great British Music Survey

It’s funny how themes crop up from week to week. Here’s another baffling media story.

Over the weekend we saw the Great British Music Survey from IPC a media conglomerate (NME, Country Life, Woman’s Own, etc.) under the headline “Women are the biggest spenders on music”. I couldn’t track down much more about the survey itself or how the figures had been calculated.

I guess these are the results from a questionnaire or telephone survey but the numbers were presented as facts and here’s the one that really stands out: “men spend more to own music (£381 annually versus women’s £327)”.

£380 a year is 10 times more than the average UK spend on recorded music, although it may be the average claimed by people who responded to this survey.

Adding Up The Music Industry 2010 (pdf) produced by Will Page and Chris Carey for PRS Economic Insight pegs wallet share for recorded music at about 0.13%. That would give Great British Music Survey participants an average income of £292,000 a year, and rake in a staggering £19 billion for UK recorded music alone.

Taken at face value the IPC figures just don’t add up without basic information about how they were gathered and calculated, and what they really represent. But like so many media statistics I’m sure we’ll see a lot more of these numbers in future.

The excellent Radio 4 programmed More Or Less calls these Zombie Statistics, data that is dead but won’t lie down.

Some not extremely disappointing facts

Sometimes I come across an article which makes me wonder if everything I think about the music industry is wrong. 12 Extremely Disappointing Facts About Popular Music gave me reason to ponder, albeit briefly, this week.

Now, I’m sure these facts are right and they are interesting but what they say and what they suggest are two entirely different things. This is quite a neat demonstration of how the media presents information for impact. It doesn’t really mean what it seems.

So Creed, who have been working their 4 albums for 15 years, are quite likely to outsell Hendrix who only recorded in his own right for 4 years, then died. Hendrix still sells hundreds of thousands of albums each year 40 years after his death. It remains to be seen whether Creed will equal him in the long term, and how about all the records Hendrix played on before The Experience?

Led Zeppelin were an albums band and Rihanna is a singles artiste. In the age of albums Zeppelin released no singles in the UK, they were happy to sell albums (singles were released elsewhere). Rihanna is working in the age of digital singles and deliberately makes frequent releases. On the other hand Led Zeppelin has sold 10 times as many albums as Rihanna (200 million to 20 million). And it’s easier to get a number one single today than it was in the 1970s. REM has sold more albums than Rihanna (83 million) and so has Depeche Mode (75 million).

Next we have a couple of Beatles stats: Ke$ha’s “Tik-Tok” sold 12.8 million to The Beatles “I Wanna Hold Your Hand” 12 million, and Flo Rida sold as many as “Hey Jude” (8 million). Are either of these disappointing? The Beatles are arguably the best selling recording artists of all time, one of the few to sell around a billion records. Flo Rida may have equalled one Beatles’ single but they had two which sold more (and “Yesterday” had over 2,000 covers).

I won’t labour the point but the conclusion is pretty obvious, if you choose the right statistic it’s possible to imply anything. And if you put a bunch of different, carefully chosen stats together they seem to reinforce each other whereas the opposite is true. So yes, Katy Perry has just released as many singles from one album as Michael Jackson did from Thriller but her sales—which the other facts suggest are important—are nothing like Jackson’s.

It’s a fun article and it made me think, and sent me off to look up some numbers, but it’s not really disappointing at all. The classic acts who get shown in a bad light by the odd comparison really were as good as we remember, and the pop acts who racked up some good numbers deserve credit too but not enough to make a real difference.

Bloomin’ Ek!

Spotify’s reality distortion field

I won’t talk about the embarrassing media event, how Daniel Ek is not a charismatic presenter or how his partners (Jan Wenner and 4 other app providers) were made to look like goons in front of the press. Or about the much more interesting Twitter #askSpotify feed which raised many good questions that went unanswered. Instead I’ll just correct a few details. When you see the Spotify gospel churned by lazy journalists allow yourself a knowing smile.

Spotify has long claimed it is the second biggest European digital music revenue stream. That would mean it either pays the music industry more than iTunes or more than YouTube. It doesn’t. There are also many digital music B2B companies who must have paid more than $150 million.

Ek makes a big deal about Spotify being a game-changer and so on. Until yesterday it was a big online music jukebox with shared playlists and now it has the extra functionality its rivals have had for some time. Before Spotify, claims Ek, the web was silent. He means before October 2008 and the web was most certainly not silent. (Pandora, which launched before Spotify, has 80 million users, 40 million of them active. Spotify has 10 million active users, so even allowing a bit of poetic license Ek is several orders of magnitude adrift.)

Yesterday Ek made a big deal about the Spotify “everything, everywhere” service. All the music you want wherever you want to play it. There are just two problems with that: they don’t have everything and you can’t play it everywhere.

Reports from iTunes Match (a slightly bigger catalogue than Spotify) indicate people find about 20% of the tracks they own missing from the Apple database. Spotify users will experience the same kind of gap left by deleted back catalogue albums. On top of that they won’t find the latest tracks from Adele and Coldplay, or the hundreds of indies who won’t supply Spotify on principle. Gracenote, the metadata database, holds the details of 100 million tracks and even that comes up short on occasion. Spotify doesn’t have everything.

But you can use Spotify everywhere? No, there is no Spotify access on your iPad or Blackberry. In fact yesterday’s music app announcement was all about the desktop, so premium subscribers who can use some mobile devices won’t be able to get the game-changing apps on their iPhones either. Spotify doesn’t work everywhere.

Ek is clearly deluded, or not too fussy about what he says. But if you want to see a reality distortion field even bigger than Steve Jobs’ take a browse through that #askSpotify feed and consider whether this really is the awesome company with happy customers you read about in the mainstream press.

Music Hall added to Music Biz Timeline

Some key dates and events from the age of Music Hall added to the Music Biz Timeline, mainly taken from the excellent Michael Grade documentary. Music Hall dominated public entertainment in the UK from the late 1840s to World War One and sowed the seeds of light entertainment and popular music. During World War One Variety began to replace the Music Halls.

Going underground (again)

The music industry of the present really is getting more like the industry of the past. The recent consolidation of the Majors takes them even further away from what is happening in music today. Music fans looking for something more than chart artists and the odd YouTube break-through act find plenty of diversity in the healthy new underground on the web.

The original music underground was born in the 1960s. Mainstream music media of the day (such as it was, basically the post-War BBC) offered only easy listening household names. There was no official radio for the music of the young so they turned to pirate radio and Radio Luxembourg.

The Beatles with the help of George Martin (and massive sales) came to run EMI rather than the other way round. The counter-culture was evident in their later work but they remained a mainstream act until The End. Pink Floyd on the other hand made a first album of psychedelic pop before morphing into a progressive rock monster fuelled by a rich underground scene in London and elsewhere. There were few Floyd singles after that and Led Zeppelin famously released only albums in the UK.

By the end of the Sixties the record industry embraced the idea of “album bands”. Other Sixties Mod and R&B acts, often supported by new indie labels like Immediate, Island and Charisma made a similar transition from chart music to “adult-oriented rock”.

Just as pirate radio, independent labels and a strong live scene brought alternative music to young people in the Sixties, the Internet is doing it today. (By the late 1960s and 1970s all the big labels had their own progressive imprints like EMI’s Harvest, Philips’ Vertigo and Decca’s Deram, a sharp move even in an industry that still served record buyers of all ages—would our teen-oriented industry be able to do the same?)

But Major labels are alert to the new competition for eyes and ears if not minds. Rihanna has sold 11,594,209 singles in the UK since 2005 deliberately releasing more records. Her manager Jay Brown explains it is no longer possible to keep the attention of the public by making an album every 3 or 4 years—she has released 6 albums in 7 years. Of course, in the 1960s it was quite normal for an act to release more than one album a year, but we’re getting there.

Deconstructing Lefsetz

I often thought about tracking one of the noisier pundits to see if their startling insights made sense over time, then last week I saw this:

Lefsetz—8 November 2011

The Myth Of The Long Tail

Just because everything’s available, that does not mean anybody wants it.

A couple of things struck me. I was sure he used to be a fan of The Long Tail and even understood it. And we all know The Long Tail doesn’t say “if it’s available people will want it.” But this isn’t just a parody of The Long Tail, it doesn’t make sense. Everybody knows marketing can flop—consumers know they don’t buy everything.

The Wired article was first published in 2004 and the book in 2006. First called The Long Tail: Why the Future of Business Is Selling Less of More and later changed to The Long Tail: How Endless Choice is Creating Unlimited Demand. Perhaps the new subtitle confused Lefsetz, “unlimited demand” is a daft thing to say.

Chris Anderson sparked a useful, if sometimes badly titled debate. Both the original article and the book have been revised. Lefsetz has name-dropped The Long Tail quite a bit, here are some early mentions.

Lefsetz—19 January 2006

And you have articles like “The Long Tail” saying that selling of less than platinum material is VERY profitable, that there’s a demand for EVERYTHING!

Lefsetz—5 April 2006

THE LONG TAIL

There’s a market for everything and fewer people want the mainstream thing.

Lefsetz—14 April 2006

For it’s a long tail world, and he who does not participate in it is doomed.

Lefsetz—26 April 2006

THIS is the long tail. There’s a demand for everything. The key is to make almost all of it available.

Lefsetz—2 May 2006

Yes, it’s a long tail world. There is demand for everything.

Lefsetz—20 July 2006

The future is long tail.

At first Lefsetz believed a caricature of The Long Tail, that there is a market for everything. Everything would sell. But we already knew that wasn’t true. The iTunes Music Store launched in April 2003 and labels reported a substantial minority of tracks never sold at all.

When the book came out some of the numbers were challenged and Lefsetz began to doubt his original version.

Lefsetz—9 October 2006

Yes, it’s a long tail world, but it doesn’t go on FOREVER! To the point where there’s demand for Little Johnny’s keyboard work.

Of course, nobody ever said that and Lefsetz knows, or at least he looked up a more accurate description.

Lefsetz—26 October 2006

The Long Tail equation is simple: 1) The lower the cost of distribution, the more you can economically offer without having to predict demand. 2) The more you can offer, the greater the chance that you will be able to tap latent demand for minority tastes that was unreachable through traditional retail. 3) aggregate enough minority taste, and you’ll often find get a big new market.

But Lefsetz wasn’t distracted by reality for long, he found it much more entertaining to throw rocks at his straw man.

Lefsetz—10 November 2006

5. The Long Tail

So everything sells. Big fucking deal. It’s kind of like blogs. Anybody can have one, but only a SLIVER of them get any page views. The point of Chris Anderson’s book is if you put it up on the Web, someone will want it. Enough to quit your day job? Good question. Probably not.

Lefsetz—30 November 2006

Too much has been made of the long tail.

Lefsetz—9 January 2007

The long tail says that there’s demand for everything, that people want a much wider swath of material than previously thought, and that via Internet distribution, it’s now available and will sell. I AGREE with that.

But hang on, now he agrees with it again, in CAPITAL LETTERS, and he read the book (a year after it came out).

Lefsetz—12 July 2007

I’m finally slogging through “The Long Tail”.

He liked it. Perhaps because he was seeing the whole picture and not just his sensational misquotes. But it didn’t last.

Lefsetz—12 March 2010

The Long Tail means everything is available, so your friends and family can buy it, not that we, the general public, care whatsoever.

Lefsetz—30 December 2010

The Long Tail was a myth.

Lefsetz—8 September 2011

You’ve been sold a bill of goods.

You read “The Long Tail” and believed a new era was upon us, an egalitarian one in which everybody got to play and be recognized, where music was plentiful and those making it survived financially...but this is untrue.

That’s the pundit’s dilemma. If you’re not shocking people every day you might get ignored. When The Long Tail was new it was “the future” but now the idea is familiar it’s “a myth”. Which is a shame because Lefsetz doesn’t need to work the sound-bite end of the business.

Debugging broken Bit.ly links

I’ve been tied up for a couple of days sorting out a URL problem. To be fair it could occur with any link shortener. If you have ever been plagued with broken Bit.ly (or other) short links this may be of interest. I have written up the incident and what I discovered here When Bit.ly links break. Along the way I had to wrestle with a not very helpful helpdesk and a Bit.ly page that could show the problem (Goo.gl does). I’m glad that’s over, although I still have no idea how it happened.

Pete Townsend, John Peel, Wayne Rosso and Steve Jobs

Pete Townsend gave the BBC 6 Music John Peel Lecture last night—I wasn’t disappointed but then I didn’t expect much. I love early Who, but not hot air:

Now is there really any good reason why, just because iTunes exists in the wild west internet land of FaceBook and Twitter, it can’t provide some aspect of these services to the artists whose work it bleeds like a digital vampire...

Townsend badly needs a music biz primer and a calculator. Apple pays the record industry precisely what they agreed—more money than anyone else has made for the Majors on the Internet. The artist’s cut goes into Townsend’s bank account via his record label and the writer’s cut via his publisher. Why should Apple do their job? Did Our Price or HMV?

And Apple is a “vampire”? What would Townsend call the distributors and record shops who sell his CDs just like Apple? They take a far higher cut and never provided the extra services he seems to think Apple should offer young musicians. He had nothing to say on the subject of his lecture "Can John Peelism survive the internet?" There is much to be said about John Peel, 6 Music and the web, but Townsend isn’t the man to do it.

Wayne Rosso also takes the anti-Apple line this week. He describes Andy Lack as a potential saviour of the music industry for resisting Jobs:

While the other guys had stars in their eyes, Andy [Sony] connected the dots and pushed Jobs for a royalty on the sale of each ipod.

Wayne Rosso is normally a good read but this is another comment in search of a calculator. A 1$ levy—as Microsoft later paid for each Zune—would give the record industry just $450 million, based on sales to date (iPods 300m, iPhones 100m and iPads 50m). That wouldn’t save the record industry—it’s down tens of billions since before the iPod launched in 2001. Online music sales only started with iTunes Music Store in 2003 and it has since paid the record industry far more than half a billion.

What Rosso doesn’t mention is that Sony had all the resources Apple had and more, but they failed to deliver web music in a way that worked. Sony bought into the music business precisely to exploit the synergy between music and technology. In his authorised biography of Jobs Walter Isaacson describes the negotiations for iTunes Music:

“Sony’s never going to figure things out” [Jimmy Iovine] told [Doug] Morris. They agreed to quit dealing with Sony and join Apple [iTunes Music Store] instead.

Since their magic bullet SDMI failed Sony have launched several music retail hubs for the Internet and mobile phones, all have stiffed. Rosso himself has a history, his P2P music service Grokster failed where iTunes succeeded (although these days the RIAA wouldn’t be quite so keen to shut a potential web music licensee down). He did the right things at the wrong time. Steve Jobs, love him or hate him, did the right things at the right time.

Pundits and cynics

Pundits cheer for the leader. They applaud mighty Microsoft, Nokia or MySpace and their world beating sales, revenues or numbers of users. Cynics shoot down the leader, pointing out flaws in the pundits’ latest darling. I don’t do much of the former but you have to bear in mind nobody really knows who’s right, until it happens.

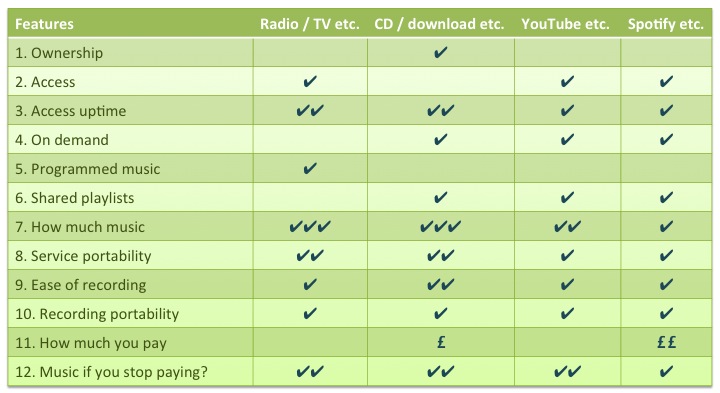

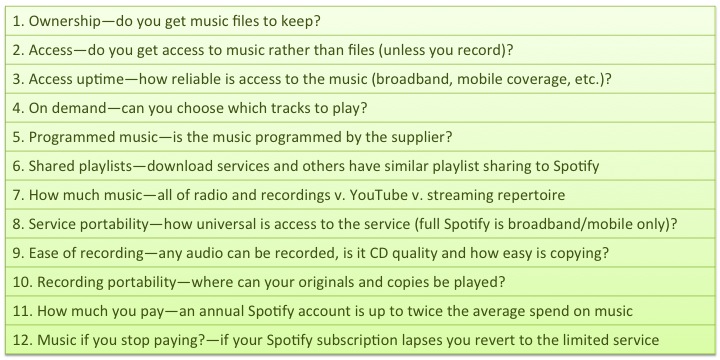

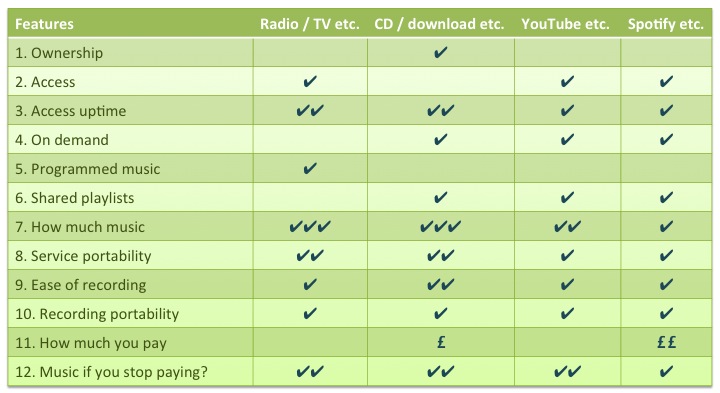

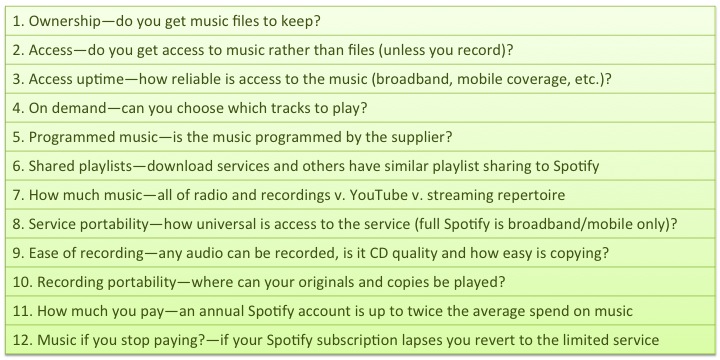

Steven Levy has an article in Wired about what I’ll call The Spottybook Theory. There are two main proposals here: streaming will have massive scale and that scale will make money. So I did a rough comparison of the features.

These examples are shorthand for general categories: radio, records, upload sites and streaming services.

Streaming has been tried for a decade and few services have survived. Even less have made any money. None have made a profit overall. If the pundits are to be believed, somehow Spotify has cracked the magic formula but it needs to get at least as big as radio. That’s their real competition, not iTunes. If you want reliable, universal access to a wide range of music there’s no alternative to ownership. At least, not yet.

Back to the future

In the 1930s there were million selling records but every act had a career on the road, in films or on the radio, sometimes all three. That’s where artists got their breaks. Music radio wasn’t yet the sidekick of the record industry, radio wanted the acts live on air whenever possible.

There were big record labels and distribution but no Major labels. The 600-pound gorillas of the music industry were managers and agents. Bidding wars involved managers building stables of artists and venues trying to attract the best acts. The stars were able to name their price for record deals and there were no long exclusive contracts. (Film studios pioneered that kind of business before it spread to records.)

Starting out was hard work and newcomers had to be good. Of course, there was always the establishment. You needed to get a gig with an existing name or work your way up through one of the entertainment empires before your manager could get you into the best venues, films or radio. But the whole industry was built the right way round, it depended on getting punters through the door. If there was a better act, a better venue or a better film in town you would have to up your game.

It seems to me this is where we’re headed again, right now. The Major labels have lost their grip on media, distribution and retail—the Internet provides all three, for everyone. Already we have a new generation of managers and independent acts. The Majors can no longer afford bidding wars and don’t control the front page of the iTunes store. Recording is once again a secondary outlet for acts who have built a reputation on the road and online.

This time round audio may not regain the traction it once had. Any band would rather have a cut in one of the Twilight films or an advert on TV than have a top ten single. The Internet is a multi-media experience. Live work is a multi-media experience. Audio is often a background for jogging, driving or web surfing. But now music has escaped the radio-friendly chart format we may even see serious listening return to the mainstream. Music discovery blogs and sites like Pandora and Pitchfork provide useful filters. Choice is no longer limited by the top 40—word of mouth is multiplied by the web.

Amplified records and radio, and cinema sound and colour, were the new entertainment technologies of the 1930s but it took decades for the incestuous grip of the Majors, MTV and radio to take hold. Technology is a wonderful thing but Web 2.0 isn’t going to throw up a new music business overnight. If you want to understand the “new music business” take a look at the way things worked back then. Let the TV talent show winners have their Christmas single. All that is just a sideshow now.

Will 25% of the world buy music?

Something Marc Geiger said on This Week In Music last week rang a bell—he forecast two billion paying subscriber accounts for some kind of music streaming at some time in the future (you’ll find it around 38:00 on the webcast).

If it had been Daniel Ek (Spotify) I wouldn’t think twice but everything else Marc Geiger said made a lot of sense. He seems to come at the music business from a similar angle to me—it’s all about artists and fans. To be fair neither Geiger nor Ian Rogers suggested this was happening next week, and they did say this kind of scale might come from new music service front-ends like Turntable.fm rather than simple playlist radio.

Now, we know the music industry has failed to do anything like that scale and they’ve been trying (sort of) for over a decade. Paying subscriber accounts are still single figure millions and as far as I know none of these businesses have ever made a profit. But that’s not what Geiger was talking about—he said once the music was available some kind of consumer layer would transform the whole game.

And this is the bell that rang. In 2006 I hung-out on an invitation-only music industry forum where they discussed mobile music among other things (as Ian Rogers mentioned this debate was common at that time). I thought there was no way to merge the user interface of a cellphone and an iPod, I just couldn’t see it. One of the members of that forum who always made a lot of sense and clearly knew a thing or two told me to wait a year and it would all be clear. He must have seen an early iPhone and as we now know he was right.

So, here we are again—or are we? A music industry bloke who makes enormous sense just drops into the conversation “two billion paying music subscribers” like your best friend might say he’s built a spaceship. WTF?

He may be right but there is a mountain to climb. Any time this decade two billion accounts would be around a quarter of the world population and one of my touchstones for music take-up is that only 40% of the UK population ever paid for music. I’m not talking about Internet piracy, this was always the rule of thumb for CD buyers. So his two billion now looks like at least half of all music buyers.

Then there’s another fly in the ointment. On average those CD buyers never spent anything like £120 a year, the current going rate for a mobile Spotify account. The average consumer spend on recorded music in 2002/3 (a record year as I say elsewhere and often) was around £50. Which means Marc Geiger’s music subscribers would spend all their money on the sons of Spotify and buy no additional recorded music at all.

In fact the ointment is full of flies: would people use just one service? would these services have all the music they want (they don’t right now)? would subscribers be happy to pay forever and keep nothing? how about those pirate economies (Russia, China, …) where the average spend on recorded music is zero? And so on…

Sadly I think that’s a mountain (of fly infested ointment perhaps) we will never get over. Geiger hopes these new web services will earn the music industry ten times what it ever earned before—which translates to our UK record buyers spending £500 a year instead of £50. Not in my lifetime. But I do remember saying something similar about the iPhone.

It’s an interesting idea. If the sons of Spotify really did that much business I’d look much more favourably on music subscriptions and I’ve been wondering how that kind of future might work. I just can’t see it though.

Edit: This is an interesting perspective from Ian Rogers at DMFW just the previous week I think. It seems there are not yet 2 billion web users so Marc Geiger’s forecast is even further ahead of its time than I thought.

Autumn Spring cleaning

The site needs updating again. Last time was December 2010 and we’ve seen a trickle of music biz changes this year from a continued recovery in single sales to the extension of the master copyright from 50 years to 70. In 2010 I took a couple of months out and checked every word but this time I’ll do it page by page.

There are also a few bits that need special attention. I originally wrote the Digital Distribution page to emphasise the many forms of digital music sharing. A lot of that is now widely understood and the page can be re-worked to focus on the main DIY and music biz angles. I learned a great deal more about SEO from the 2010 update and have some additions for the Search Engines page. Over the year I have also collected quite a long list of additions for the Glossary, Beatles’ Business and others.

In the mean time, here’s the first refurbished article The New Music Biz Model.

Spottybook

So, Facebook Music is now a week old and my scepticism is about the same. Spotify has added over a million accounts, so for them at least it was a worthwhile exercise. A small fraction of the Facebook population care about music but people still can’t help dreaming about those 800 million Facebook accounts. There are less than 20 million streaming accounts and less than 10 million paying subscribers worldwide.

There was a very good discussion on This Week In Music*—it’s about 45 minutes. Somewhat buzzword bingo (curation, filters, gatekeepers, engagement, content resolution, music discovery, …) but well worth a look.

They seem fairly clear that “music discovery is now legally free” but let’s not forget, UMG said very recently they are seeking to switch from ownership to access, i.e. from iTunes to Spotify and Co. Although why they want to cut their own throat I have no idea. The crazy thing about Major labels is they now find themselves trying to re-establish music branding. Record labels used to be brands and people used to buy Island, Immediate, Charisma and others on the strength of their catalogue and roster.

These days it’s only indies and some Major imprints (urban or R&B mostly) that are contemporary music brands. (Of course, there are many jazz, folk and classical labels who still stand for something too.) The Majors own hundreds of imprints that have lost their meaning over the years, labels that could still be trusted filters to represent something customers and fans can recognise. Instead they seem happy to stand behind Internet names like Spotify and shovel a mountain of undifferentiated music into the world.

Spotify is now making credible headway towards their Year One target of 50 million USA accounts but it remains to be seen whether they’ll keep the momentum of the past week. If this was just a sideshow I’d be quite happy—what worries me is it seems to be the Big Music strategy: to swap chart radio for streaming at the cost of music sales, when iTunes and many others have shown that sales of singles can be grown substantially online.

Music sales earn a lot more than Spotify or YouTube and people do still prefer to buy. I can’t see streaming supporting the record industry, Facebook or otherwise. Talking of which, the much vaunted Timeline turns out to be a feed your Friend’s apps can post to, and some adverts. I was hoping Facebook might show your account activity in order. Oh well.

*(Incidentally, TWIM is one of my favourite music biz news sources alongside CMU, Music Ally, Digital Music News and Buzzsonic.)

The pundits rapture… I shrug

Last week was all about Facebook, or rather Facebook talking about Facebook dreams into the big pundit echo chamber.

Alarmingly, commentators spoke about a revolutionary answer to web music monetization problems. Some even claimed last year’s Facebook F8 had transformed the Internet already. What? Against my better judgement I had a look.

Pundit World is a completely different planet to the one I’m on. Facebook is a big social site with 500 million or maybe a billion users but that’s all. Last week they talked about real time music features although they still can’t get notifications to work on their own app. My Facebook web site page is too buggy to rely on and musicians regularly report fan pages get blocked. That’s no basis for music solutions on my planet.

And what did Zuckerberg offer? Auto-updates about music you’re streaming from some sites and posts from some music ticketing sites. Of course, music pundits’ nom du jour Spotify was dropped too but if you’re not on Spotify or whatever else gets posted there’s no read-across from your friends’ music to yours.

Zuckerberg is taking his lead from contemporary Internet hit sites like Spotify and Turntable.fm but the music industry is way too fossilised to allow an open social music experience. For that you need to take your iPod round your friend’s house, or go to a gig.

There are two audiences for puffery like this: investors and users. I think investors will be happy, they got tons of media time and megatons of hype but from a user point of view it could be Apple Ping—will anyone care? Musician-user streaming money is negligible so there’s nothing for them—they’d probably prefer Facebook pages that work, or someone to pick up the phone when they don’t.

These two articles summed up F8 for me. Andrew Orlowski in The Register and Anthony Bruno in Billboard Biz.

Of course the Facebook timeline was also announced—they might stop messing around with posts and give you chronological order. That one is straight out of the software developer’s marketing manual: how to make a blindingly obvious correction look like a new feature.

Robert Heinlein sums up the record industry

I was reading press reports and blogs about the EU phonographic (master) copyright extension and I came across this excellent quote posted by G Thompson (@alpharia on Twitter) among some comments on Techdirt:

"There has grown up in the minds of certain groups in this country the notion that because a man or corporation has made a profit out of the public for a number of years, the government and the courts are charged with the duty of guaranteeing such profit in the future, even in the face of changing circumstances and contrary public interest. This strange doctrine is not supported by statute nor common law. Neither individuals nor corporations have any right to come into court and ask that the clock of history be stopped or turned back, for their private benefit." -- Robert A. Heinlein, Life Line, 1939

I’m never sure if old quotes that capture something fundamental about the world are reason to feel reassured or to despair.

The other reason CDs don’t sell

The debate about piracy is somewhat like Global Warming, the Media only admits two points of view, for and against. The pirate view or the big label view. In Helienne Lindvall’s recent article for The Australian she argues the big label version: piracy is killing the music industry.

Helienne is a good journalist and music piracy certainly exists but I’m no freetard and when I look at the Record Industry Crisis I see different reasons for it.

In the mid-1990s everybody knew MP3 was coming. Over the previous century the record industry had come to specialise in content rather than technology and now saw the need to control technology again. Their solution SDMI was broken on delivery and the Internet adopted MP3 unfettered.

The labels’ Plan B was to refuse MP3 licenses, so they sued Napster and the first “iPod”, the Diamond Rio. They continued to plan their own web retail (Pressplay and MusicNet) while their business was slipping away.

Supermarket muscle had slashed big label margins on chart albums and now they were beholden to two new monsters on the web: first Amazon then Apple. (Some of the names in the USA were different—Walmart, Best Buy, etc.—otherwise the story there is the same.)

The full High Street price of a CD album in 1999 was about £15—by 2003 it was below £10. Distribution margins were also hit but the new retail giants forced big labels to take a cut too. In turn they cut staff and cut artist rosters.

In 2003 the iTunes Music Store opened and Internet music really began to cannibalise physical. 2002/3 was the peak UK record industry year for physical sales (MP3 had been on the streets for 8 years). It was after iTunes that album sales declined and single sales grew. To date albums are down about 50% and singles up over 600%.

The Record Industry Crisis is all about the loss of CD album sales and it seems to me a 7-fold increase in single track sales means buyers are cherry-picking album tracks instead of buying the albums.

Another negative effect of the web on big record labels was the massive expansion in broadcast channels. They used to dominate access to a limited TV and radio mainstream. On the web they’re just another content provider.

However, the big labels tell us none of this matters so much as “piracy” although big commercial infringers have been largely ignored apart from Pirate Bay, Gnutella and LimeWire. Instead the BPI (and their IFPI partners) sued thousands of individual file-sharers and blamed ISPs. Russian MP3 sites are still trading. YouTube and Grooveshark continue to build their businesses on content they don’t own.

The way I see it articles condemning pirates as the nemesis of the record industry only give them power they don’t have and influence they don’t deserve.

Defence against the Dark Arts

Promotion and marketing are two words much abused in music business discussion online. People often say they use social networks for promotion or marketing when they mean something much less definite. Promotion is making people who might be interested aware, and marketing is getting them to buy. There’s no half-way house.

Let’s assume I have a good band and music people want to hear (by no means givens and in my case not actually true). We all know what promotion does. If a venue holds 300 and I can only count on 50 I might use a third party to promote the event and get the other 250 through the door. If there were still only 50 people at the gig it would be daft to call him a “promoter”.

Likewise if I have a run of 1,000 CDs and I can move 250, I might ask a specialist to help market the remaining 750. Again, if I have to stack 750 CDs in the garage I can be sure no marketing worthy of the name has occurred. Importantly, if these “promotion” and “marketing” guys don’t deliver I won’t use them again.

The true worth of promotion, marketing or advertising has always been notoriously hard to pin down but for us it’s fairly easy. Did new people get to know what we do? Did more people hear our music? Did we sell more tickets? That’s all that matters. A mailshot is normally binned by over 95% of recipients and those are terrible odds if you’re collecting followers who just might care. They probably won’t.

Did I get more email addresses? Or Facebook friends? These are the wrong questions. Obviously. You can’t do promotion or marketing through a browser unless the right people are looking and listening.

The same applies to everything else a band is trying to do: move albums on Bandcamp, sell singles on iTunes, get heard and seen on stage or the Internet. The crucial aspect often missing in web chat about promotion and marketing is the audience. Sufjan Stevens can confidently promote a new single on Facebook where he has 380,000 real fans, but Joe Bloggs can’t. He could easily reach some social network contacts but are they really fans? Will they buy his music or tickets? Will re-vamping his social media change that?

You have to promote and market where your audience can be found, in a way that gets their attention. The most expensive promotion and marketing on Earth—Superbowl half-time—would be useless for almost every new band I can think of. There are no promotion techniques, however awesome, that work for everyone.

These days you can buy Facebook friends and Twitter followers in chunks of 10,000 or more. They’re not expensive. Or you can work social media day and night following and friending-back, hashtag spamming, posting, DMing, photo tagging, blogging, using The 7 Promotion Tips Every Musician Should Know and joining every new social site that pops up. Either way you’re probably wasting your time.

Social media promotion and marketing tips are often useless for the very people who are most likely to try them. The Internet is the worst place for a new act to try and get attention, it’s too crowded. Local press and radio, clubs, gigs and word of mouth will be far more effective until an act really has a fan-base. The exception is music forums, blogs and zines relevant to the audience. Until there is traction there, in your town and your genre, it’s pointless pumping Facebook.

Of course, you can and should have music, videos and information anywhere that helps what you’re doing in real life. But don’t waste hours on your laptop trying 9 Social Media Marketing Secrets. Do what works and discard what doesn’t, but do the important stuff first, like having an act people will kill to see. Then you’ll never feel the need for 15 Tricks That Will Boost Your Fan-base.

Blogging again

I had a blog here when I started the site about 10 years ago, then I switched to longer articles. In January this year I thought Twitter and Facebook might fill the gap but although Twitter works well there are some thoughts that are too long for tweets. So here I am blogging again. Let’s see how it goes.