Being my philharmonic reminiscence: a salmagundi of germane illustrations, salient interludes and adventitious excursions whereby diverse prosopographical affairs are conclusively arranged to the ready convenience of all and sundry.

I was born the same year as the charts.

Today they sing their kids to sleep with Smells Like Teen Spirit; Dad sang Ragtime Cowboy Joe, Don’t Fence Me In and The Sunny Side Of The Street. The post-war record format upheaval was over but my parents still had a lot of pop and classical 78s. Record players had four speeds: 78, 45, 33, and the never-used 16 for speech. Their vinyl was mainly show tunes like South Pacific and big band re-issues. Dad sang around the house and liked Louis Armstrong, Bing Crosby and Frank Sinatra. Pat Boone’s 45 For A Penny (1959) was popular with the children for its B side: Wang Dang Taffy-Apple Tango. We were already flipping over the hits to find the cult tracks.

I lusted after the blue pearl snare drums in the percussion cupboard at school but there were only six so the tambourine, maracas or (worst of all) triangle were more common. Children without instruments clapped—I did a lot of clapping. Music lessons were usually with the BBC Light Programme and I remember singing Aiken Drum, and Bill Bones’ Hornpipe about a sailor who danced round the world with his cat. That folk song with its exotic story and many verses fascinated me and I learned it by heart. We also practised what would later become idiot dancing, in the Music And Movement class (“Find a space, now imagine you’re a tree!”—all without drugs as far as I know).

I have a strong memory of seeing O What A Beautiful Morning (from Oklahoma!) on a black and white TV at home. That would have been in the 1950s but I don’t know when it was first televised (the musical film was released in 1955). It’s possible the version I remember was re-staged for TV, film musicals (Rogers and Hammerstein, etc.) were enormously popular then. Around the same time I watched a lot of The Lone Ranger with its stirring Rossini introduction and voice-over (A fiery horse with the speed of light, a cloud of dust and a hearty Hi-Yo Silver! The Lone Ranger! With his faithful Indian companion Tonto, the daring and resourceful masked rider of the plains led the fight for law and order in the early West. Return with us now to those thrilling days of yesteryear… The Lone Ranger rides again!). An early foretaste of spaghetti Westerns perhaps.

We learned The Walrus and the Carpenter set to music for a school concert but I was dropped before the gig for singing flat. It was another epic which I enjoyed hugely nevertheless.

As primary school finished The Animals released House Of The Rising Sun in the summer of 1964. I was hooked when I saw them on Top Of The Pops (or perhaps Ready Steady Go). It shot to number one. I was aware of The Beatles but bands often played covers on TV and any four lads in suits looked the same. Chewing gum cards told me George played lead and John played rhythm but I didn’t know what that meant. I liked the La Bamba riff on Twist and Shout but until I saw The Animals I was indifferent to pop. Under the influence of The Animals, schoolfriend Paul and I formed a group. I remember talking endlessly about House Of The Rising Sun and he painted our logo on a bass drum, but that was as far as The Reptiles went. Paul had a wicked groove and a penchant for soul.

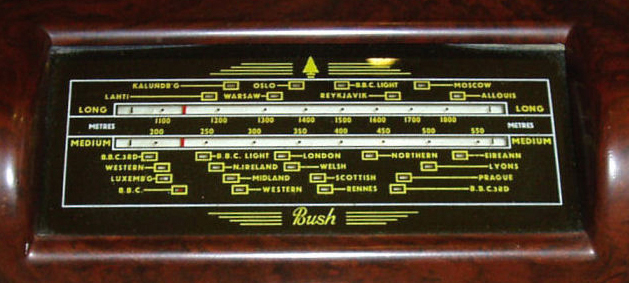

My secondary education was a golden age. Pirate radio played all the great music from 1964 to 1967 when it was outlawed and replaced by the insipid government station Radio One. Transistor radios were banned at school, but so was smoking, long hair (“It’s over your collar, boy!”) and of course, short hair, Doc Martens and anything unconventional. At least we still had music lessons. I particularly remember Saint-Saëns Danse Macabre and the day we listened to I Feel Fine.

In Spring 1965 I had a minor operation and spent what seemed like months at home recovering and listening to the radio. The chart from those weeks is permanently etched in my brain: Roger Miller King Of The Road, Donovan Catch The Wind, Rolling Stones The Last Time, Unit 4 Plus 2 Concrete and Clay, The Seekers I’ll Never Find Another You, Tom Jones It’s Not Unusual, Bob Dylan Times They Are A-Changin’… I was fortunate we didn’t have daytime TV.

On March 1 1966 the BBC showed The Beatles at Shea Stadium, filmed in August 1965. We were invited to watch the concert by a neighbour who had a television and amid the screaming frenzy it dawned on me The Beatles were exceptionally famous. By that time we had seen Help! at the cinema and I’d got the joke in Rubber Soul which they recorded when they came back from America. The album sleeve was hanging in Soundtrack’s window for months. Incredibly, Revolver was released in August just a few months after the Shea Stadium concert was shown here (with songs from Beatles For Sale and Help!). For a long time the earliest Beatles’ single I liked was Ticket To Ride another track from Spring 1965.

As if set free by pirate radio a string of classic singles followed The Animals: The Kinks You Really Got Me, The Stones (I Can’t Get No) Satisfaction, The Beach Boys Good Vibrations, Procol Harum A Whiter Shade Of Pale, Spencer Davis Somebody Help Me, The Byrds Mr Tambourine Man, The Monkees I’m A Believer, and The Beatles Day Tripper and Paperback Writer. I taped Johnny Walker on Radio Caroline breaking the law on August 14 1967 at midnight with All You Need Is Love.

An old classmate from primary school Steve and I bunked off extramural Latin and he showed me the chords to Nowhere Man on his Spanish guitar (a decade later I found him gigging around Essex in a decent rock band called Crossbreed, playing a very nice Les Paul Custom). At one time or another I had piano and violin lessons but I didn’t learn much that way. I picked up my piano from Lady Madonna and Hey Jude, and classmate Pete gave me his old Winfield acoustic guitar. We wrote a couple of wistful songs. Another friend Mark and I were caned for playing The Moody Blues Go Now on the school piano. Perhaps there were too many bum notes.

I wrote a lot of poetry to pass the hours I spent in church. It was something you could do in your head—strong rhythms and rhymes were easy to remember. I always had a few poems in the school magazine. My great friend Chris and I were the English swots in our class at school. He was Syd Barrett and I was Paul McCartney, but I wanted to be Syd.

Dad put Frank Sinatra Strangers in the Night and Acker Bilk Stranger on the Shore on the jukebox when we stopped at a motorway café on an overnight coach trip to Durham in 1966. Those tracks were the last echoes of his kind of music in the charts. There was a bike gang at another table looking dangerous. They chose rock ‘n’ roll. One Saturday afternoon in August I played The Troggs With A Girl Like You—the autochanger arm up so it would repeat. After about twenty plays he made a joke about it. The single belonged to my mod sister Liz and she introduced me to the Small Faces All Or Nothing and other club hits including Stax and Atlantic soul. She also lent me a boyfriend’s copy of The Beach Boys Greatest Hits which I played to death. In December I bought my first record The Who Happy Jack (6/9d) which Mum frisbee’d into the wall after one too many repeats on the autochanger. It didn’t survive—Keith Moon would have been proud.

Dad put Frank Sinatra Strangers in the Night and Acker Bilk Stranger on the Shore on the jukebox when we stopped at a motorway café on an overnight coach trip to Durham in 1966. Those tracks were the last echoes of his kind of music in the charts. There was a bike gang at another table looking dangerous. They chose rock ‘n’ roll. One Saturday afternoon in August I played The Troggs With A Girl Like You—the autochanger arm up so it would repeat. After about twenty plays he made a joke about it. The single belonged to my mod sister Liz and she introduced me to the Small Faces All Or Nothing and other club hits including Stax and Atlantic soul. She also lent me a boyfriend’s copy of The Beach Boys Greatest Hits which I played to death. In December I bought my first record The Who Happy Jack (6/9d) which Mum frisbee’d into the wall after one too many repeats on the autochanger. It didn’t survive—Keith Moon would have been proud.

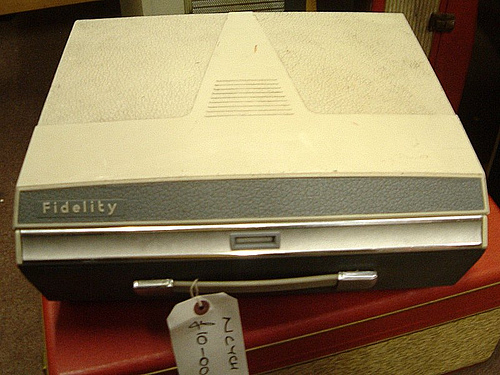

In 1967 I saved 10 guineas on my paper round (5 months at 10/6d week) to buy a portable transistor record player/radio. I was glued to the radio and made home ‘radio programmes’ on Mum’s Fidelity Playmaster reel-to-reel tape recorder with the two Marks and Pete from school. Some were a tribute to I’m Sorry I’ll Read That Again; others a homage to Radio Caroline. All my money seemed to go on records and The Beatles double was a stretch at nearly £3.

In 1967 I saved 10 guineas on my paper round (5 months at 10/6d week) to buy a portable transistor record player/radio. I was glued to the radio and made home ‘radio programmes’ on Mum’s Fidelity Playmaster reel-to-reel tape recorder with the two Marks and Pete from school. Some were a tribute to I’m Sorry I’ll Read That Again; others a homage to Radio Caroline. All my money seemed to go on records and The Beatles double was a stretch at nearly £3.

Dad had worked in radar during the war and taught me about electronics and valve circuits. I cadged record players and parts—a friend of Mum’s through the Church taught me how to fix earth loops. I interfered with anything that had a radio or amplifier and scrounged obsolete valve radios for free as people upgraded to modern transistors. One big cabinet radio came from a friend of Dad’s who was making ornate chairs for an African parliament building—his shed was full of incredible carvings.

At school I did some backstage work on a school play The Long And The Short And The Tall. Pete and I set up the lights and had our wiring redone by a professional after a fire brigade inspection. I rigged up a tape recorder inside a radio case with a switch so the actor could cue the right noises. There was a lot of radio tuning atmospherics with an occasional faux-Japanese “Johnny, Johnny, British Johnny. We you come to get!”

I put a Schaller pick-up on the Winfield guitar and played it through a Dansette record player. The Dansette had an EL84 valve amp and sounded great. I wrote some songs with Chris and he did a good imitation of Jimi Hendrix with maximum feedback through three record players.

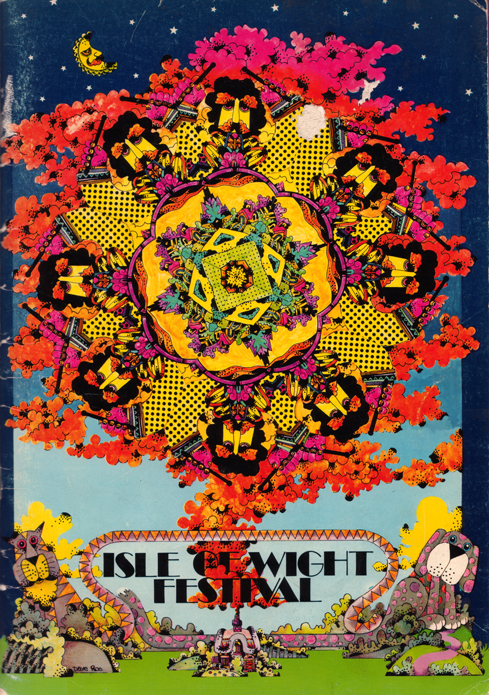

Chris and I listened to Zappa, Bowie, Pink Floyd and Curved Air on his parents’ (fully transistorised) Philips stereogram at full volume with the French doors wide open. The picture of the roadies with all the band’s gear on the cover of Ummagumma made me want a van full of amps, guitars and drums. It was another step down the road that started with The Animals. Straight after my driving test we drove up to see Woodstock (filmed the previous year) at The Empire, Leicester Square. I was amazed by many of the performances and bought the triple album. That summer we made an expedition to the Isle Of Wight festival with Anthony from school, and I particularly remember The Who and Procol Harum whose rock and roll encore was outstanding. Also that year the Cream farewell film was a stunning experience in spite of the dreadful sound and overblown solos. My brother Sid played me Blind Faith on a trip to Rome in 1970 and Ginger Baker has been a favourite ever since (I nearly broke my ankle in 1992 dancing to Ants In The Kitchen). By that time I was at college, avoiding work and wondering how to get a job in music.

Chris and I listened to Zappa, Bowie, Pink Floyd and Curved Air on his parents’ (fully transistorised) Philips stereogram at full volume with the French doors wide open. The picture of the roadies with all the band’s gear on the cover of Ummagumma made me want a van full of amps, guitars and drums. It was another step down the road that started with The Animals. Straight after my driving test we drove up to see Woodstock (filmed the previous year) at The Empire, Leicester Square. I was amazed by many of the performances and bought the triple album. That summer we made an expedition to the Isle Of Wight festival with Anthony from school, and I particularly remember The Who and Procol Harum whose rock and roll encore was outstanding. Also that year the Cream farewell film was a stunning experience in spite of the dreadful sound and overblown solos. My brother Sid played me Blind Faith on a trip to Rome in 1970 and Ginger Baker has been a favourite ever since (I nearly broke my ankle in 1992 dancing to Ants In The Kitchen). By that time I was at college, avoiding work and wondering how to get a job in music.

At college I took a science course with a mandatory arts subject, I still had no idea what I wanted to do and it never occurred to me that music was a real option. Miss French was a very old and excellent pianist and taught 2 or 3 of us whatever we wanted under the vague heading of Music. I brought my Beatles sheet music and she helped me read it, showing up howlers in the the hack transcription. She told me about syncopation—the difference between the printed version and what I played by ear from the recording of Martha My Dear. She died many years ago but her pencilled notes live on in my Beatles song book. I loved being in the music cubicles practising piano, hearing the flutes and violins from next door and reading the music students’ noticeboard. The college and pub scene was a lot of fun but I should have taken music full time.

At college I took a science course with a mandatory arts subject, I still had no idea what I wanted to do and it never occurred to me that music was a real option. Miss French was a very old and excellent pianist and taught 2 or 3 of us whatever we wanted under the vague heading of Music. I brought my Beatles sheet music and she helped me read it, showing up howlers in the the hack transcription. She told me about syncopation—the difference between the printed version and what I played by ear from the recording of Martha My Dear. She died many years ago but her pencilled notes live on in my Beatles song book. I loved being in the music cubicles practising piano, hearing the flutes and violins from next door and reading the music students’ noticeboard. The college and pub scene was a lot of fun but I should have taken music full time.

Chris arranged a trip to see Curved Air supported by Mick Abrahams at the Royal Festival Hall (June 25, 1971) and I saw my first synthesizer. I saw The Who again at the Oval on September 18, 1971 headlining a memorable all-day benefit for Bangla Desh with America, Cochise, The Faces, Mott The Hoople, Atomic Rooster, Quintessence, Lindisfarne, and The Grease Band. As I left to get the last train home Won’t Get Fooled Again echoed around the streets of SE11. At college I was writing songs in earnest and swapped notes with Phil who also wrote and played blues harp. He introduced me to Uriah Heep, Yes and Gentle Giant and would talk through a whole prog rock album describing the tracks and production. His description of Fragile was so good I had to buy it.

I played guitar and sang in a church group where Sid wrote music. It was good fun although I’m not religious. Rehearsal night was best; I was still playing the Winfield and we swapped T. Rex riffs in the break. With my increasing armoury of valve amplification and homemade speaker cabs I entertained at a church hall disco for my sister’s bemused Girl Guide troop. They expected pop singles but got Who’s Next, Jeff Beck and Led Zepellin II until the vicar intervened. Black Sabbath was probably the last straw.

The best gig of 1972 was Mott The Hoople on 25 June. Ian Hunter autographed my girlfriend’s arm in lipstick and climbed into a truck much bigger than Pink Floyd’s. “Never forget Mott!” he urged. “Er, no” I replied weakly, but I never did.

College ended and I got a job on the buses where a number of errant musos took refuge. I needed money for proper gear to join a band. Putting an unwieldy cart before a feeble horse I didn’t realise my songwriting wasn’t up to the job; for some reason I always wanted to write as well as play. But with an Eko Ranger 6 and 12, a CSL Les Paul copy, a Center 4x12 cab, a home-made 2x15 and Sound City 50, Triumph 100 and HH amps, I nearly had a van-load of gear.

The first proper band I formed with Kev (bass) and Bob (drums) from the buses ran into a brick wall of inconsequence and petered out. History has forgotten we were called Wombat and sometimes Earshot. Syracuse Flagday, an abandoned follow-up with Alex from the buses on drums, was notable only for my decision to write better material before trying again. Kev, Bob and Alex were good but we just didn’t have the songs.

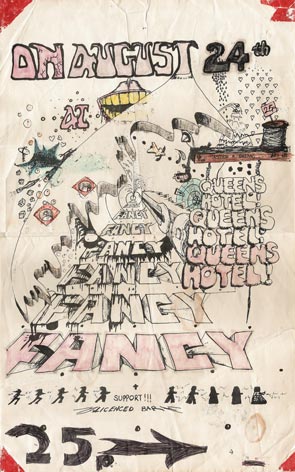

Bob Banasiak, another friend from the buses and a year younger, had already formed a band that was everything we weren’t. Fancy were the best local band before the Feelgoods and put out an indie single Starlord b/w Brother John (Sticky STY3, 1973). Bob cautioned me in the ways of label points and territory deals, giving me the first inkling about the music biz. He made demos at home on a Revox, which looked like a good idea. Pretty soon he left the buses to work full time in several pro bands. He was (and probably still is, playing with Cherry and the Bulldogs on the West Coast somewhere last time I heard) an extraordinary natural guitarist.

Bob Banasiak, another friend from the buses and a year younger, had already formed a band that was everything we weren’t. Fancy were the best local band before the Feelgoods and put out an indie single Starlord b/w Brother John (Sticky STY3, 1973). Bob cautioned me in the ways of label points and territory deals, giving me the first inkling about the music biz. He made demos at home on a Revox, which looked like a good idea. Pretty soon he left the buses to work full time in several pro bands. He was (and probably still is, playing with Cherry and the Bulldogs on the West Coast somewhere last time I heard) an extraordinary natural guitarist.

In Summer 1973 Dr Feelgood had a residency at the Cloud Nine disco on Canvey. Wilco still had long hair and wore jeans—before the pudding-bowl and black. Their amps were pristine cabaret Vox on chrome stands. I saw them once or twice most weeks—they were terrifyingly good. At The Kursaal Ballroom in December I joined several hundred assorted hippies and greasers to see Mott The Hoople yet again, this time with support band Queen. All we knew was the guitarist had made his axe from an oak fireplace. Prepared for the gentle irony of Ian Hunter, we were taken by surprise as rampant frontman Freddie upstaged Mott in a zebra leotard (and further costume changes!). It was a virtuoso tour de force. Queen were in their prime between Queen II and Sheer Heart Attack. Their encore was a Led Zep meets Mozart caricature* of the tired rock ‘n’ roll medley (normally Johnny B. Goode and Route 66). Utterly priceless.

In Summer 1973 Dr Feelgood had a residency at the Cloud Nine disco on Canvey. Wilco still had long hair and wore jeans—before the pudding-bowl and black. Their amps were pristine cabaret Vox on chrome stands. I saw them once or twice most weeks—they were terrifyingly good. At The Kursaal Ballroom in December I joined several hundred assorted hippies and greasers to see Mott The Hoople yet again, this time with support band Queen. All we knew was the guitarist had made his axe from an oak fireplace. Prepared for the gentle irony of Ian Hunter, we were taken by surprise as rampant frontman Freddie upstaged Mott in a zebra leotard (and further costume changes!). It was a virtuoso tour de force. Queen were in their prime between Queen II and Sheer Heart Attack. Their encore was a Led Zep meets Mozart caricature* of the tired rock ‘n’ roll medley (normally Johnny B. Goode and Route 66). Utterly priceless.

After various jobs including an enjoyable (and lucrative) stint at a fun fair in the style of That’ll Be The Day I finally cracked and got a proper day job in 1975. I sold my stage gear and left home, keeping Earshot Kev’s homemade peardrop electric guitar and a Triumph Leo 7 Watt valve combo. We put together a covers band called The Anticlimax Blues Band with Ken from the fun fair on vocals and did a half hour set of 13 numbers (including Dylan’s Hurricane) but our old school Spencer Davis and Animals tunes were no longer fashionable when punk hit town.

After various jobs including an enjoyable (and lucrative) stint at a fun fair in the style of That’ll Be The Day I finally cracked and got a proper day job in 1975. I sold my stage gear and left home, keeping Earshot Kev’s homemade peardrop electric guitar and a Triumph Leo 7 Watt valve combo. We put together a covers band called The Anticlimax Blues Band with Ken from the fun fair on vocals and did a half hour set of 13 numbers (including Dylan’s Hurricane) but our old school Spencer Davis and Animals tunes were no longer fashionable when punk hit town.

To my surprise the day job was OK and I went to work in computer systems where I met like-minded people, learned a lot and had enormous fun. I couldn’t afford studio time, £10k for an 8-track Studer or even a couple of grand for a Revox, so I recorded my new songs at home on an Akai GX 4000D reel-to-reel with left/right over-dubbing. A Colorsound Fuzz Wah pedal, Maxon bass booster and Maplin Drumsette (a £67 kit for an electronic preset drum machine) provided the backing. Brother Hugh wielded the occasional bass, pen and soldering iron.

At long last I thought my songs were ready for the big time and recorded as AVO with Hugh on Arbiter bass, and Baz Bravado (solo) changing names in the hope of fooling unimpressed A&R men at Magnet, Chrysalis, A&M, Jet, Polydor, CBS, EMI, Rough Trade and Stiff. Some of the songs were pretty good but the new wave had already peaked as the Seventies ended and I started an impressive collection of rejection letters. Geoff Travis (Rough Trade) wrote the best: “Sorry Rob, I don’t like this stuff” on a torn off scrap of paper. It almost made the effort worthwhile.

My songs were more popular at work and I formed what was intended to be a band with Roger and Kevin, but ended up as a long term collaboration with Kevin. All three of us became music technology junkies and experts in the latest home studio gear. We spent a lot of time in music shops and at trade exhibitions. In 1984 I entered the 8th Annual Synthesizer Tape Contest run by Roland with my epic composition Doctor Moonthrush Meets The Ant People on SH-101, MC-202 and TR-808. I like to think it was ahead of its time. I got this nice Roland pocket-tool for entering.

My songs were more popular at work and I formed what was intended to be a band with Roger and Kevin, but ended up as a long term collaboration with Kevin. All three of us became music technology junkies and experts in the latest home studio gear. We spent a lot of time in music shops and at trade exhibitions. In 1984 I entered the 8th Annual Synthesizer Tape Contest run by Roland with my epic composition Doctor Moonthrush Meets The Ant People on SH-101, MC-202 and TR-808. I like to think it was ahead of its time. I got this nice Roland pocket-tool for entering.

With better gear—a Les Paul Standard, Rickenbacker 4001 bass, Tascam 244 Portastudio, and a series of drum machines and synths—we badgered the Majors, indies and local press with more demos. Our covering letters were sometimes better than the songs. “We can’t compromise, our music won’t let us,” wrote Kevin. “Competent but unmemorable,” wrote the local paper who couldn’t tell if we were serious or not. How we laughed.

With better gear—a Les Paul Standard, Rickenbacker 4001 bass, Tascam 244 Portastudio, and a series of drum machines and synths—we badgered the Majors, indies and local press with more demos. Our covering letters were sometimes better than the songs. “We can’t compromise, our music won’t let us,” wrote Kevin. “Competent but unmemorable,” wrote the local paper who couldn’t tell if we were serious or not. How we laughed.

When our combined arsenal of machines was wired up and running we’d switch off the lights just to watch the displays flashing in the dark while sequencers played a helicopter in a rainstorm manned by mutant jazz robots. It was very cool but history failed to even register we were called The Waste Band, Screw The Tap and many other names (not forgetting Dowager’s Hump, an imaginary Heavy Metal band). A series of talented, trendy and infinitely more serious bedsit synth players beat us into the charts.

In 1985 computing and music paid back in a small way. At that time new patches for synths were printed in music technology magazines and had to be entered laboriously by hand. To speed up the process and hoping to sell some software I wrote a type-entry DX7 editor for Commodore 64 and SIEL MIDI interface called Vole. A good typist could enter a patch sheet in about 30 seconds—on other editors it would take all afternoon. On the DX7’s lavish 32 character screen it took all day. Our local music shop had a copy permanently on demo, I sold a few more and I still use that library of DX patches stashed in my TX802. The voice editor machine code is the most satisfying thing I ever did with computers.

The inward stream of rejection letters finally overwhelmed the outward flow of demos but I carried on writing and recording at home.

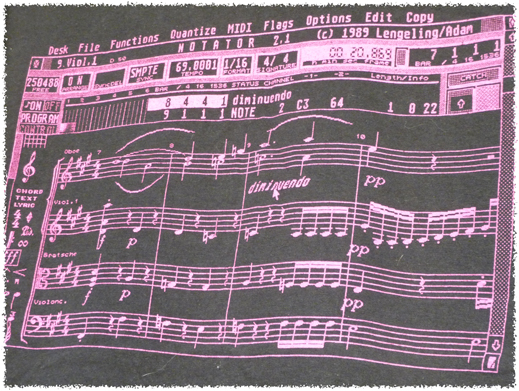

I upgraded my Commodore 64 Steinberg Pro 16 to Atari C-Lab Notator synched to tape with Unitor. Atari/C-Lab was the best computer music workstation I ever used. I later tried the Macintosh packages—Logic, Opcode and Performer—but abandoned music computers completely in the early Nineties. In that lifeless, lumbering software it was as though tedium and bewilderment had been packaged for home use. To this day I avoid computers for recording and prefer to use hardware for sequencing and audio.

When MIDI-based composition and performance arrived in the Eighties it was a boon for home recording but never as good as multi-tracking audio. Synth acts like Howard Jones and Thomas Dolby worked wonders with machines but my favourites of the era were still guitar bands, Dire Straits, XTC, The Cure and The Smiths. Technology worked best to my ears in the hands of people like Peter Gabriel, Japan and Talk Talk, but organic bands remained favourite. The Nineties were rather flat on the mainstream music scene and I rarely relate to anything in the charts since then, much preferring the likes of Bevis Frond, Olivia Tremor Control and other bands who thrive under the radar.

I spent the 1990s writing songs and music, and got quite good at it, occasionally working with Kevin. I also got the hang of recording and explored how the music business worked in more detail. This is when I drew the first sketches of the infamous music biz diagrams you’ll find throughout the site, to help me understand how royalties would work if I got any songs published. If I had known what library music was I would have approached them with my epic MIDI compositions but my Theme For A Soap About Lobsters remains unused.

I discovered the Internet and ended up working in e-Commerce and management consultancy. I made some good contacts and came very close to throwing everything into the day job—I was head-hunted for a high profile government e-Commerce job but wisely decided that 24x7 insanity wouldn’t suit me. Eventually I got frustrated with business theory and office politics and went back to making computer systems.

I discovered the Internet and ended up working in e-Commerce and management consultancy. I made some good contacts and came very close to throwing everything into the day job—I was head-hunted for a high profile government e-Commerce job but wisely decided that 24x7 insanity wouldn’t suit me. Eventually I got frustrated with business theory and office politics and went back to making computer systems.

The new web economy promised to change business forever but the two-fingered riposte of the Dot Com Crash changed it all back again. The old-fashioned fundamentals were still true and my distrust of Web 2.0 was born a decade before it happened.

In a fit of pre-Millennial tension I made another attempt to get my songs used commercially. ISA, SWG, GISC and Bandit offered to smooth the way to success. I joined up, then bailed out rapidly as I discovered I knew more than they did. Planning a renewed assault on the world of publishing I organised what I had learned about the business. My nephew Steve worked at BMG in the 1990s, later ran his own record label and managed a truculent megastar (he now works in merchandising). He helped me fill in the gaps and I began to think about the nuts and bolts of a DIY release, planning the steps needed to do a proper job.

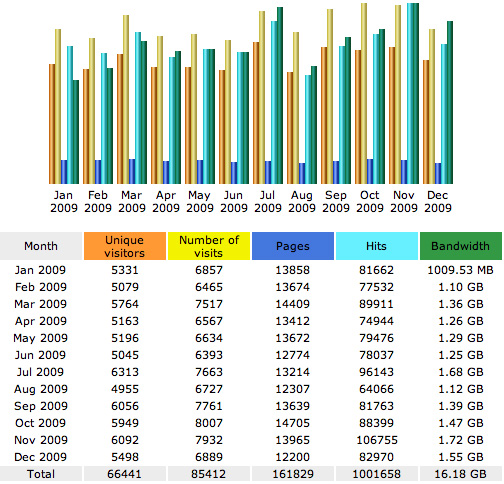

Soon after 2000 I suddenly got very ill and my entire life came to a standstill. Lying in bed week after week—under the influence of very strong drugs—the idea of Bemuso took shape. I planned a help site for the growing DIY music community alongside my Alien Wireless (folk rock) and Austin Torpedo (country rock) recordings. It made sense to share what we had learned now the Internet made it so easy. As I recuperated in 2002 I built the site with help from nephew Tony and brother Mark. The success of the DIY pages was a pleasant surprise but after Napster and MP3.com the traditional music industry was sicker than I was. The site grew rapidly from half a dozen pages to well over a hundred. Things were changing fast and soon DIY downloads were as popular as homebrew CDs.

Soon after 2000 I suddenly got very ill and my entire life came to a standstill. Lying in bed week after week—under the influence of very strong drugs—the idea of Bemuso took shape. I planned a help site for the growing DIY music community alongside my Alien Wireless (folk rock) and Austin Torpedo (country rock) recordings. It made sense to share what we had learned now the Internet made it so easy. As I recuperated in 2002 I built the site with help from nephew Tony and brother Mark. The success of the DIY pages was a pleasant surprise but after Napster and MP3.com the traditional music industry was sicker than I was. The site grew rapidly from half a dozen pages to well over a hundred. Things were changing fast and soon DIY downloads were as popular as homebrew CDs.

The music side didn’t go smoothly. USA telecomms firm Alien brought out a product called Wireless and bagged the dot com address, and a group of Norwegian rockers cornered the Scandinavian market as Austin Torpedo... well, it is a good name. My next music project will have to be called something else. I have enough good songs to make quite a few CDs and I hope to put some extras online, and possibly podcast. Video is easier, and almost inevitable today. But I found myself spending a lot more time on the site than I did on the music, exploring the music industry upheaval with new friends and business contacts on the Internet.

Since Bemuso appeared on the web I’ve been able to compare notes with many more musicians and writers inside and outside the music business. Their wisdom and experience on a range of subjects has added to my observations from 30 years loitering in the foyer of success. The diagrams and text here were put together over almost two decades and they’re still growing as I discover more about how it all works and how to work it. There are several new sections in the wings that need polishing before they go online and of course the world of online music changes month by month.

As a result of my work on Bemuso I’ve had numerous job offers and I get frequent invitations to collaborate in online music business ventures. More to the point, I have had the opportunity to advise artists about royalties, copyrights and contracts, and it’s very satisfying when we get a good result.

Today, I live happily ever after with my wife and our cats in Essex, sometimes resisting the urge to buy more equipment with flashing lights. Bemuso is a great success and helps hundreds of people every day. Universities, colleges, Wikipedia authors, the Musician’s Union, royalty societies, and many other music organisations regularly use material from the site. Numerous other businesses regularly nick my material without permission and explaining copyright to them provides a little light relief.

In January 2011 I started using Twitter and Facebook, and when Facebook turned out to be useless for blogging restarted my blog here to talk about the ever-changing music biz. I still write songs, research the music biz and have nothing else to do but study, write and record these days. Who knows, I might even get some music finished this year, or maybe next.

twothousandandtwelve@bemuso.com (Sorry, I don’t have a clickable email address because the spambots always find it.)

*Google tells me the Queen rock ‘n’ roll medley included Jailhouse Rock, Stupid Cupid, Bama Lama Bama Loo, Be Bop A Lula, Shake Rattle And Roll, and Big Spender.