The past decade has been dominated by theories about the Internet and life after CDs. Sales are down 50% and falling, and profits are gone. Of course, this isn’t a music business problem it’s just a mainstream record industry problem. The Majors have stumbled, so what happens next?

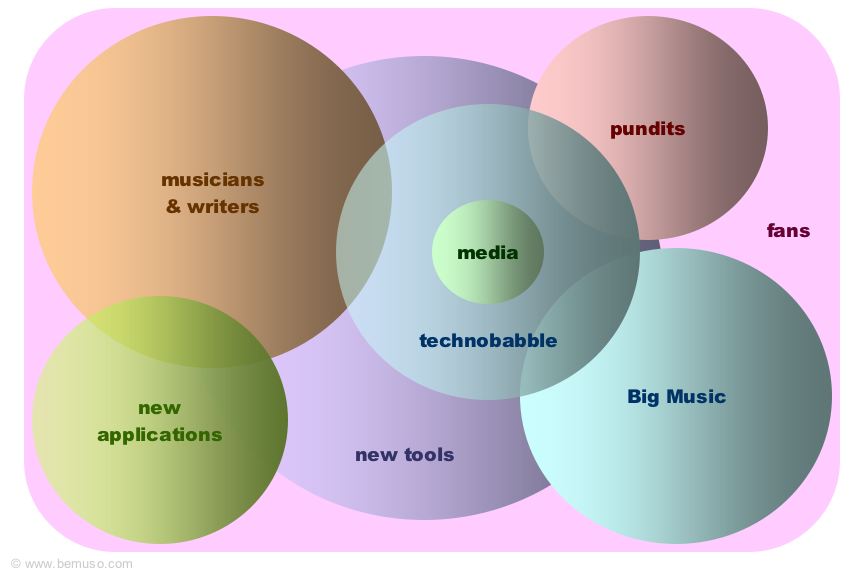

The whole idea of business models comes from Harvard Business School, and the music industry is overrun with gurus and consultants. SXSW and MIDEM used to be mostly about music but now they speculate about the new business model and 7 Tips For Exploiting Social Networks. There are endless statistics and seminars but how much is fog or misdirection? Before we design the future we might take a good look at the past.

Before we consider a “new model”—what was the previous music business model? And are we right to expect such a thing again? A single general model is only possible when business is integrated in some way. Could the diversity of the Internet conform to one business model now the Majors control a smaller share?

| William Hazlitt |

|---|

| Rules and models destroy genius and art. |

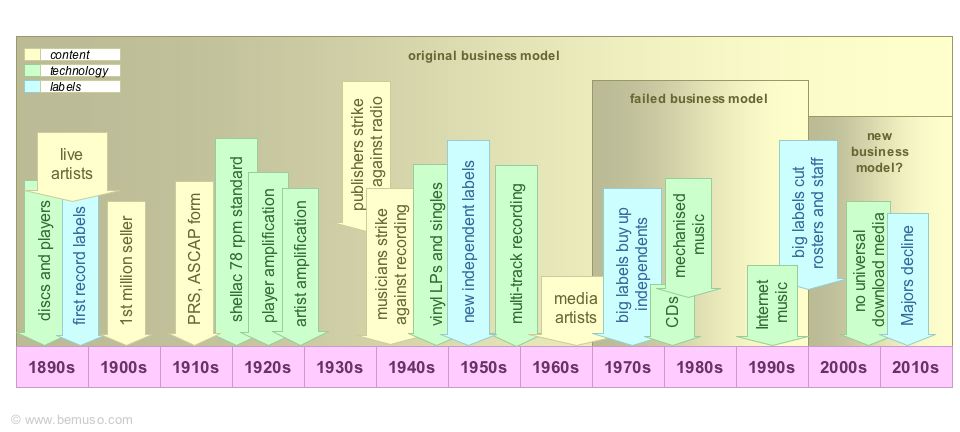

There have been two significant “music business models” in the audio recording era so far. The first model began around 1895 with the marketing of mass produced audio records (discs). The second ran approximately from the formation of Warner Communications and Warner Elektra Atlantic distribution under Kinney (1970) to the 2000 crash. So far, a third model—the “new music business model”—remains a myth.

| Features of the original model 1895 to present |

Features of the second model 1970 to 2000 |

|---|---|

|

|

There are exceptions. Before 1970 Berry Gordy (Tamla Motown) was featuring unknowns backed by established session performers and writers, and there were The Monkees of course but UK labels’ ability to launch beginners didn’t become widespread until later. After 2000 the second model lingered, notably with TV phone-in talent shows.

I won’t explore every aspect of the record industry: classical music, jazz, folk and blues are inherently live and were largely established before recording. And I may gloss over the extraordinary recording careers of Patti Page, Shania Twain, Def Leppard and Elvis Costello, among many others, but you can test your own favourites against my argument.

Physical properties of sound and electricity were discovered by the early 19th Century and technology pioneers tried various contraptions. Thomas Edison developed recordable cylinders, unaware of the demand for pre-recorded music. Emile Berliner got two important things right: people wanted music and lots of it. He made discs (easier to duplicate and store than cylinders) and ignored user-recording. Discs also turned out to be louder, an important feature for acoustic playback. Edison plugged away with cylinders for 30 years but he backed the wrong horse.

And music for the discs? Berliner used popular musicians—dance halls and theatres were full of them—it was easy to see who would sell, they were popular. Nobody designed or predicted this business model, it was simply what worked at the time (and for the next hundred years). Many alternatives flourished briefly and then failed. Most just failed.

This is a fact often overlooked by the record industry. There was popular music before there was a record industry and without it there would be no record industry. Recording boosted Caruso’s income but he already had a career in the music industry.

Record companies developed and owned the technology, and sold (or licensed) players and records. Source material (what we call “content”) came from live entertainers of the day. As early as 1900 the record industry was repackaging black dance music for white audiences. Before World War Two they called this “race music” and it was the basis of R‘n’B (a term coined by Jerry Wexler in 1948).

So the record industry around 1900 would be very familiar to us, and we would also recognise the rash of copyright and patent suits. The new record industry was lucrative and grew fast. Pioneers (mainly Berliner and his engineering partner Eldridge Johnson) fought off lawyers for almost a decade, gave us the Victor record label and a growing record industry.

|

|

|

||

| © Wikimedia Commons | ||||

Innovation came across the Atlantic. Significant growth occurred first in the British Empire (which still existed) because the American Pacific market was smaller. Licensees and subsidiaries of Berliner technology sold dance music, classics, opera, musicals and other popular songs throughout Europe and Asia. An early example of white boys playing black music—The Original Dixieland Jazz Band—shifted a lot of records between 1917 and the mid-1920s. Others had million sellers as early as 1907. Radio was still young with no real need for records and, like recording, mostly featured the real world. The iPod of its day was the Victor Victrola, a passive (acoustic mechanical or orthophonic) record player, but a change was coming—amplification.

Radio spread rapidly alongside the record industry and there was clearly a demand for more than local entertainment. For a time, in the early 1920s, radio seemed to be a threat to the recording industry.

By this time there were finally workable amplifiers for cinema, radio and record players. Around the same time higher quality electrical record cutting became possible. These technologies incorporated solutions for many separate problems and film, radio and record industries owned the patents. Victor’s original disc patents expired by 1918 and shellac 78 rpm discs had become standard (various speeds were used prior to the 1920s). In the mid-1920s a variety of dual-mode Orthophonic Victrolas, Electrolas and Radiolas with amplifiers became available. But new-fangled record players weren’t cheap and during the Depression around half of all record production went to jukeboxes.

| Pre-war record label artists in-house |

|---|

| In the decade before World War Two, and for a while after, record labels often retained their own in-house bands and artists. Ray Noble was the house band leader at HMV. Decca had Roy Fox and Arthur Lally. Jay Wilbur was house band leader for the Crystallate group, notably the Rex label and its predecessors. Harry Hudson was at Edison Bell for the Winner and Radio labels. These writers and performers were hired to make dance band recordings for labels who found it difficult to satisfy demand using headline acts alone. The stars of the day were too busy to spend as much time in the studio as the labels might have liked, they were earning a living on the road and the radio. A record catalogue could accommodate a lot more material than a band would need to play live. These record label artists weren’t developed in-house. Ray Noble, for example, was a concert pianist and composer of popular songs who had won a Melody Maker contest for dance band arranging. So these labels were hiring very capable musical directors to work with some of the best players and singers available. Recording studio MDs, session fixers and players have been used to varying degrees from the 1890s to present day, unusually pre-war label house bands became as well-known as some of the performing artists they backed on record. Ray Noble accompanied artists such as Gracie Fields, Jack Buchanan and Jeanette Macdonald. |

In 1930, fronting dance bands, singers like Al Bowlly developed an intimate style of singing using microphones. Bing Crosby and Frank Sinatra soon followed. Previous technology had favoured music loud enough to record easily: dance, opera and classics. Paradoxically amplification allowed more subtlety. In parallel technology enabled other electronic instruments: keyboards and guitars.

Live radio shows with popular artists were still a big draw but broadcast use of records and recording was inevitable. This trend was resisted by composers and musicians. In 1941 ASCAP asked higher publishing royalties from radio but they had to settle for less after 10 months. Two successful musician strikes led by trumpeter James Petrillo followed. In 1942 AFM sought compensation for jukebox and radio performances and in 1948 a short strike improved musicians’ royalties from TV. Powerful vested interests feared the impact of new technology but when the dust settled restrictive practices would not impede progress.

Within two decades the industrial momentum of the war and progress of technology led to new, high fidelity, record formats. In the 1930s record industry boffins had perfected stereo vinyl discs playing at lower speeds.

In 1948 Columbia Records launched 33 rpm 12 inch vinyl records and in 1949 RCA Victor introduced 45 rpm 7 inch vinyl records—long players and singles. (EMI ceased 78 production in 1960.) The record industry once again set universal player standards and technically literate post-war enthusiasts took up the public demand for music on record and radio, with independent labels like Chess, Atlantic and Elektra.

Separate “artist development” was still unheard of. Musicians like Quincy Jones had to learn their chops and get in front of an audience. If you weren’t on stage you wouldn’t get hired. Records, radio, and now TV and cinema, were a distant aspiration but first you had to make it in bars, clubs, dance halls and theatres. Artist development (if any) was the responsibility of managers but more often it was sink or swim.

After a short time in the studio Elvis Presley was making local hit records before touring, getting too big for Sam Philips’ independent Sun Records and moving to RCA for $40,000 (including a personal bonus of $5,000). Artists continued to get signed for their live appeal.

From the early 1950s popular music was increasingly targeted at the new singles charts, but stage musical soundtracks remained big earners from the 1940s to the 1960s including: Oklahoma!, My Fair Lady, West Side Story, The Sound Of Music, and Hello Dolly! Stage, film and TV productions were often the biggest hits on record. (This trend continued with Fame, High School Musical, Glee and many more on the small screen.)

Towards the end of the 1950s impresarios like Larry Parnes renamed and packaged live acts like Marty Wilde, Billy Fury and Georgie Fame to cash in on the American trend set by Elvis, Buddy Holly and Little Richard. By 1960 the record business was the same as it had always been: find talent, record and distribute, but there was some evidence of artist development emerging at EMI. Norrie Paramor used studio musicians on early Cliff Richard sessions while the Shadows were taking shape but it wasn’t a lengthy process. Cliff And The Shadows had hits and appeared on pop TV from the start.

The Major record companies as we now know them had yet to emerge from the mass of small independents and larger groups who controlled distribution.

This was the decade when British bands took R‘n’B back to the USA. Again, EMI tidied up The Beatles but they charted within weeks and had a number one record with their second single. The Rolling Stones were selling out the Crawdaddy Club in Richmond, and The Beatles themselves were selling out the Cavern in Liverpool, before they were signed. Numerous independent labels signed live bands during the Mod R‘n’B era (Small Faces, Kinks, Who) and rock (The Yardbirds, Cream, Led Zeppelin). In America both approaches were evident: acts like the Beach Boys pursued their own vision while producers like Phil Spector increasingly moulded artists commercially. Around the end of the Sixties two new trends became clear.

First was the birth of the corporate industry as bigger labels hoovered up independent labels formed over previous decades. Eventually these corporate record companies became what we call the Majors.

Second, the combined effect of radio, television and singles charts led labels themselves to take more control of pop acts. Music in this format appealed to a younger audience and there were no clubs or dance halls where an audience of children could separate the wheat from the chaff. The era of so-called artist development had arrived and The Monkees pioneered formula-driven chart success (developed by a TV production company rather than a record label). A clear distinction arose between chart pop and album music.

| Development—the recurring fantasy of the record industry |

|---|

| Major labels like to emphasise their creative contribution in developing the record industry. In the 1980s they claimed a hand in the development of CD and even charged their artists for the imaginary effort. And today they like to say they have developed artists over several decades (who will cultivate new artists when the Majors are gone?). It’s true many artists today were plucked from obscurity and groomed for stardom but it’s unusual for a record company to be responsible. All the leading examples of manufactured acts (Boyzone, Atomic Kitten, Girls Aloud, etc.) were developed by management or production companies. Most often a producer will shop them to a smaller label before they get picked up by a Major. Lady Gaga was dropped by Def Jam before being rediscovered by Interscope, a fellow label of the Universal group. Her exuberant reprise of Bowie and Madonna was never planned at a record label A&R desk. Only their accountants have that much imagination. |

So now, the original business model that had lasted 75 years was joined by another: acts with no pedigree were tailored to a singles chart template. Labels could grow by working radio and the charts, and buying smaller record labels. Those changes would turn out to be important but something equally significant had already happened. Recording technology was no longer developed by the record industry, it had been taken over by consumer electronics companies and the next innovation would be made by Sony and Philips. (Sony and Philips did have music recording divisions but their technology companies were separate. The CD wasn’t exclusively for audio or music, there were computer, data and video formats too.)

Over the next three decades big labels increasingly signed chart acts from management, production and development companies.

But the basic principle of the original model—find popular artists and market their recordings—remained. Even after 1970 Queen, The Police, U2, Radiohead, Oasis, Coldplay and others established themselves on the road before generating substantial earnings for the Majors. Like Elvis they occasionally needed initial development by a smaller label but artist development was down to the bands and their management.

Throughout the 1970s American AOR (The Eagles, Journey, Boston), British prog (Genesis, Pink Floyd, Yes) and rock (Led Zeppelin, Black Sabbath, AC/DC) dominated the album charts. But Major labels, fuelled by income from mergers and record sales, developed massive in-house A&R, media and promotion departments, seeking ready-made acts to fit chart pigeonholes.

In the Eighties an unexpected bonus in the form of CD re-sales inflated the Majors further and the outrageous promotion of singles as loss-leaders for albums reached a peak with MTV videos costing hundreds of thousands apiece.

Taking dance ideas from hip-hop DJs, producers now used drum machines, sequencers and synths to construct records for newly developed artists. Samples, loops and computer tools generated quick, undemanding hit templates for teen stars. The mechanisation of music and in-house production tempted thousands of bedroom artists to short circuit live performance and “get signed from a demo” but very few succeeded.

In the mid-1990s the web became popular and MP3 technology spread rapidly online. There was no way to license copyright MP3 files from the Majors. At the same time record retail began to migrate from traditional high street shops to supermarkets and the Majors were forced to reduce their margins.

In the mid-1990s the web became popular and MP3 technology spread rapidly online. There was no way to license copyright MP3 files from the Majors. At the same time record retail began to migrate from traditional high street shops to supermarkets and the Majors were forced to reduce their margins.

The record industry had prepared a strategy for the Internet but they were out of touch with technology. World CD sales peaked in 1999/2000 and suspicious of online culture Major labels failed to get Internet commerce underway before Apple opened the iTunes Music Store in 2003. They still have limited sources of online revenue but things look far worse in the shadow of bygone CD sales than they actually are.

The spike in CD sales between 1990 and 2000 was more of a windfall for the record industry than a birthright. Album tracks could not be bought separately at the time and music fans re-bought 4 decades of post-war popular music and centuries of classical. Even without the Internet it’s unlikely the CD boom would be sustained or repeated. The Majors sold albums online because they wanted to, they sold singles online because they had to.

In 2003 a record number of UK albums were sold for an average of £9.79, a disaster for the Majors. Although each album cost less than 50p to manufacture the industry had allowed overheads to eat up the rest. They had got used to asking £15. On top of that single sales had halved compared to 1998. The reason for this is simple, you couldn’t buy singles online but you could download them—a blunder that was soon corrected by iTunes.

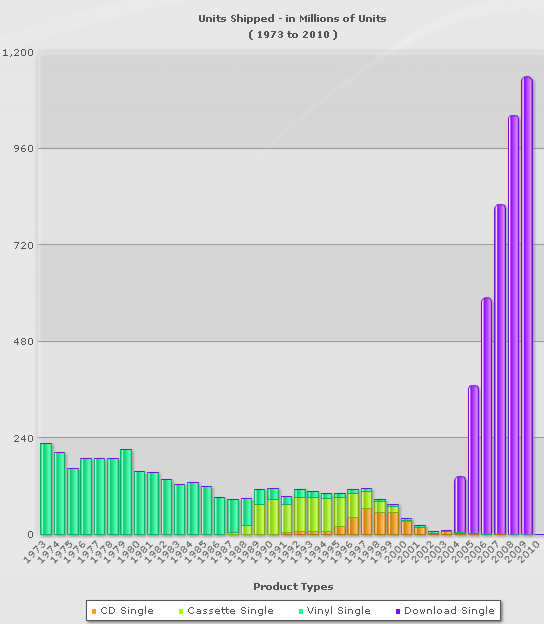

The Majors looked at the decline of CD, matched it with the growth of filesharing and concluded: that must be where the money went. But nobody ever paid for every song they listen to, so why would listening online be different? And now single tracks are available to buy sales records are broken every year. This chart is from Digital Music News.

The record industry remains viable but the abnormally high margins of LP and CD are gone. Majors are carrying far too much weight to make money from individual track sales even though they still dominate national radio playlists.

| J B S Haldane |

|---|

| This is my prediction for the future—whatever hasn’t happened will happen and no one will be safe from it. |

You could argue that selling records—the core of the old industry—is hardly a business model, and I wouldn’t disagree. But remember, until 1895 it wasn’t an obvious business at all. Audiences expected to be present. The term “live music” would have been baffling. It is also useful to differentiate labels recording live acts (whether live or studio) and corporations manufacturing radio-friendly content. It is the latter that is now in serious trouble.

It is tempting to say the Majors’ mistake was selling cheap mechanical pop to 12 year olds but it wasn’t only that. Chart pop is an expensive game calling for massive investment upfront (the real developers have to be bought out and unknown acts need lots of publicity) and there is no guarantee of success, so it didn’t help. Neither did they crash because they lost control of technology, in a way that was farsighted if premature. Nor was it label bosses taking millions in bonuses when their companies were making a loss, although that happens too.

Those things hurts the bottom line but don’t add up to the current slump. The record industry’s own favourite excuse—filesharing—can’t be to blame either. The Majors slashed their rosters, staff and releases after 2000. If you’re not releasing or promoting as much you won’t sell as much. Then, starting in 2003, single sales in the USA rose to 6 times their previous peak and they’re still climbing. The recovery began with the availability of single tracks online. While blaming filesharing for the decline, can the record industry really expect album sales to hold up next to a sixfold rise in single track sales? Both singles and albums are available to buy but sales of single tracks are way up and albums are way down. That means albums were going down anyway and that is the only thing that really hurts.

What really did for the dinosaurs was bloat. They weren’t prepared for the many-pronged attack on their margins that happened in 2000. They were only prepared for never-ending growth of album sales. Recording artists still sell (see the Indies) but control of broadcasting, format and retail is history.

The old model was built on ownership of technology and mass production but Apple, Dell, HTC and Panasonic now control that. There are no Internet playlist meetings so the Majors can no longer sell records on their own terms. The market has slashed their profit margins. Their momentum can only last while people buy CDs and master rights remain, or until they get down to fighting weight for the real world.

Independents (XL, Domino, Warp, etc.) run a far tighter ship and tend not to spawn expensive media artists in-house. They are more likely to sign live acts using the core of the old model (K T Tunstall—Relentless, Adele—XL, Arctic Monkeys—Domino). Big acts at the end of their Major contracts are inclined to go it alone these days. The Majors say they made these stars but as we’ve seen that’s not true, they promoted popular records—sometimes expensive imitations of earlier successes—and were handsomely rewarded with the lion’s share of sales revenue and royalties.

The second model failed for the Majors in 2000 when they lost their grip on the supply chain (radio, distribution and retail). What is left of them will soon be reduced to publishing and digital. How much of an industry can be supported by talent shows, teen stars, single downloads and streaming licenses is unclear. From the musician’s point of view this was always a sideshow. Nobody was ever going to make them the next Justin Bieber.

So who wants a “new model” anyway? The record industry would really like something that puts them back on the 1990s CD gravy train but that won’t happen. They have no natural place in music, a freak sequence of technologies merely gave them a fleeting role. (I hope this jog through the past has shed some light on the reasons why.) And among fledgling artists there is a hope that some “new model” will magically bounce them into the spotlight. But for artists there were only ever two models: be a good live act; or be a good media act. And of course the pundits love talking about the “new model” but their output is measured in column inches rather than record or ticket sales.

So what is the future record industry model? It’s the original model: smaller labels will find popular artists and market them (often without the help of Big Media). Big labels need big margins and they are long gone. The tools have changed (Britney Spears’ Hold It Against Me video earned $500,000 in product placement) but the rules are the same. Artists now have many better ways to reach the public and find fans. The tunnel vision of the Majors and the constraints of mainstream commerce are optional after all. There is no new formula. Do Imogen Heap, Radiohead, Trent Reznor or Jonathan Coulton consult business models? The hare-brained schemes of the pundits look very like the business school roots of the Majors’ corporate golden age—plausible and perhaps lucrative for a few but ultimately a dead end.

Of course, a lot will happen on the Internet—new tools for communication, broadcasting, distribution and retail but no new business model. Even one-man labels have been done before.

|

||||

| © Bemuso.com | ||||