Music is rarely recorded on analogue media these days. Vinyl and tape are the last analogue media in production and vinyl is the last to be distributed. Soon the only remaining analogue distribution medium will be radio.

At the same time this is the final step in the artists’ and writers’ journey from local clubs and dance halls to the global music market.

Digital distribution doesn’t just mean selling downloads from an online record shop. There are many distribution systems for digital audio and video, including digital cinema distribution (RealD). Software distribution is digital, so are online electronic books (eBooks) and audio programmes (Audible.com), ringtones and even sheet music (Musicnotes.com). CDs and DVDs are another form of digital distribution. Photography is now mainly digital and the iPad provides a platform digital multimedia subscriptions (including magazines and newspapers).

Digital distribution isn’t just iTunes, or MP3 and P2P—digital products are transferred throughout the entertainment industry.

Music catalogues, soundtracks and master recordings are distributed digitally under license in the games, broadcast, film and music industries. These are known as business-to-business (B2B) applications.

Digital warehouses are the core of the digital media business. They hold licensed content in various formats for distribution to media and retail businesses. Here are a few of the big music aggregators:

| Digital warehouse | Owner | Outlets |

|---|---|---|

| MediaNet Digital | (was MusicNet) Baker Capital private equity | Yahoo!, MTV Urge, Virgin, HMV |

| Nokia Music | (was OD2 and LoudEye Corp.) Nokia | Nokia MusicStore |

| RedDotNet | Alliance Entertainment Corp., Inc. | USA kiosk systems |

| Digital Distribution Domain | DX3 Technologies | Musimob |

OD2, Europe’s pioneer (started by a consortium including Peter Gabriel) was sold to American warehouse Loudeye in 2004 and is now the Nokia Music Store (2007). Apple, Napster and Real Networks operate their own warehouses.

| Digital warehouse | Retail portal |

|---|---|

| Apple | iTunes |

| Napster | Napster |

| Real Networks | Rhapsody |

Broadcasting networks like the BBC and record label CD libraries probably hold the biggest digital music catalogues but these tracks are not all licensed for general distribution or retail.

Independent aggregators have a similar role to the big warehouses, handling more titles and artists but distributing to lower volume outlets as well as the bigger ones.

Independent aggregators tend to be global.

| Download aggregator | Based in | |

|---|---|---|

| 7 Digital | 7 Digital Media | UK |

| AWAL | Artists Without A Label | UK |

| CI | Consolidated Independent | UK |

| DMI | Digital Musicworks International | USA |

| DRA | Digital Rights Agency (now The Orchard) | USA |

| EmuBands | EmuBands | UK |

| Indie Mobile | Indie Mobile | UK |

| IODA | Independent Online Distribution Alliance | USA |

| IRIS | IRIS Distribution | USA |

| Musicadium | Musicadium | Australia |

| TuneCore | TuneCore | USA |

| PIAS UK | PIAS Digital (was PIAS Vital) | UK |

Some online music hubs also offer digital distribution as part of their direct-to-fan integration services (alongside social media dashboards, merchandise, event management, metrics, etc.).

Some online music distributors also act as aggregators, and supply downloads to other aggregators and retail sites.

Although not a distributor, it’s worth mentioning the rights broker started by AIM (MusicIndie Rightsrouter). Now run by RoyaltyShare in San Diego they have some interesting information about digital administration.

Digital jukeboxes are well-established and were the first business selling virtual records to the public to make money. These days they tend to be integrated with gaming and gambling in dedicated card or coin-op multi-function kiosks, often providing ringtones and other downloads.

| Company | Jukebox type | Country |

|---|---|---|

| ECast | software platform: music, films and games | USA |

| TouchTunes | complete dedicated coin-op music system | USA |

| MAX FIRE™ | complete dedicated coin-op system | Europe |

These are commercial jukebox systems for restaurants and bars, not PC jukebox software. There are many others.

Kiosks are close to the old model of buying CDs in a shop (with some pluses to offset the minuses). Fast dedicated networks download the tracks and special terminal hardware burns CD-Rs, and prints booklets and inlays. It’s not much different to buying conventional CDs (the best of these are 16-bit 44.1 kHz CD-Rs) and you can make your own compilations but there are some drawbacks.

Kiosks are still not very widespread but there have been recent developments.

P2P uses the Internet network and some client software to move files directly between web users. Any digital material can be distributed using P2P—it isn’t mostly or only a music medium. There are commercial services on P2P, not just pirates. To say P2P is wrong is like saying motorways or telephone systems are wrong because they have illicit uses.

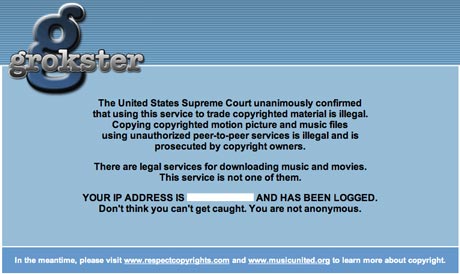

There used to be many P2P applications (KaZaA, Grokster, iMesh, LimeWire, Gnutella, Morpheus, eDonkey, etc.) but they have been implicated in music and video piracy. In 2004/5 a spate of court cases resulted in large fines and many services were suspended. The Supreme Court ruled that P2P services could be infringing if they incited illegal copying. As a result the big P2P sites are (2006/7) restructuring and implementing new controls although some may be gone forever. Some of the earlier P2P applications are still going but the most popular P2P technology now is BitTorrent.

The volume of Internet music sharing is often used to estimate piracy or to forecast download sales, but it’s a false comparison. File-sharing is more like radio, and there are many legitimate downloads that don’t represent lost sales:

Major labels have licensed their catalogues to several P2P services including PeerImpact and Mashboxx. Mashboxx was developed by Wayne Rosso (ex-Grokster) using Snocap software developed by Shawn Fanning (ex-Napster). Mashboxx identifies and blocks unlicensed files, and offers legal substitutes. However, although audio fingerprinting technology is now widespread the proposed P2P services have failed to materialise.

From March 2004 to December 2005 Loudeye operated a P2P poisoning (digital content protection) operation called Overpeer. On behalf of bigger labels and trade bodies Overpeer flooded P2P with fake files and fake upload libraries. Alongside other freelance poisoning this certainly had an effect on the quality and reliability of P2P sources. It is possible the closure of Overpeer in 2005 was to prepare for the big labels’ own P2P services.

All Internet music distribution is digital.

There are 100,000 audio and 25,000 video podcasts on iTunes Music Store alone. Podcasting uses RSS to find new shows on your choice of sites, and jukebox software to update your player as normal. These standard web and jukebox functions are coordinated using software (see Podcast Alley or iTunes) downloading content overnight to update your player for daytime listening off-line. The growth of podcasting in 2005/6 was a phenomenon but most listeners (2007) don’t subscribe to regular programmes and the term “podcast” is often mis-used for simple downloads.

Illegal sites have been closed after legal action by industry bodies, but some remain. Action by trade and intellectual property organisations continues. These are the big cases.

| Case | Brief summary of events so far |

|---|---|

| Napster 1 |

|

| Puretunes |

|

| AllofMP3 |

|

| Weblisten |

|

Thousands of DIY artists distribute their work from their own web sites, and use a combination of Internet facilities to share and collaborate. This allows fans to get out-takes, sketches and alternative versions as well as retail tracks. There are some good examples on the DIY artist list.

Professional artist sites are often run by the labels and their music files may come from a digital warehouse such as 7 Digital Media.

Many DIY and indie artists use community sites based around genres and geography. They provide a common platform, a shop window, and forums for communication.

Social networking sites are not primarily for music distribution but they have become important places for artists to post their tracks.

Compared to buying CDs—standard media, standard players and no need for back-ups—buying music online is complex, and keeping a downloaded library isn’t straightforward.

Major label retail sites are limited to specific countries because of territorial licensing but most DIY and indie artist downloads are available world-wide, either because the artists are more flexible or don’t charge.

To buy tracks from a Major label retail site (iTunes, Napster, etc.) you may need both an ISP (the site knows the country from the IP address) and credit card from that country. Some tracks are available in one country but not in another, and prices differ even from the same parent company.

Major labels first put their music online in 2000 and now license over 300 retail sites. Indie music has been online longer, there are thousands of indies and many more DIY artists. Download variations include:

Retail sites often include reviews, biogs, interviews, charts, articles, radio and interactive content (ratings, forums, feedback, etc.) to attract visitors and fans.

Deals vary widely and change almost daily—check the latest situation online. Some sites are deliberately inscrutable and you might find more about them on Google than their own pages.

Hardware suppliers and digital distributors offer domestic streaming services direct to systems such as D-Link MediaLounge™ Wireless Media Player, Sonos Digital Music System and Pinnacle Systems ShowCenter™ without the need for a personal computer.

Major label tracks licensed for sale online used to be protected by digital rights management (DRM) software controlling:

EMI and UMG announced some DRM-free options in mid-2007 and all the Majors licensed DRM-free tracks to Amazon MP3 in 2007/8. DRM is no longer used to control downloads but is till used in online subscription services.

These were the main DRM systems, roughly in order of popularity (value of sales/turnover).

| Maker | Audio format | DRM | Software jukebox | Retailer | Hardware player |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Apple | AAC (MP4) | Fairplay™ | iTunes | iTunes Music Store | iPod |

| RealNetworks | Real Audio | Helix/Harmony | Real Player | Rhapsody | various |

| Microsoft | WMA (ASF) | Plays for sure™ | Windows Media Player | Most services now DRM-free or discontinued | various |

| Microsoft | WMA (ASF) | Zune™ | Zune™ | Zune Marketplace | Zune™ |

| Sony | ATRAC* | Open Magic Gate™ | SonicStage | Connect discontinued in 2007 | MiniDisc |

| *ATRAC was discontinued by Sony in mid-2007 | |||||

Some of these systems were complex. Sony also has components called NetMD, Hi-MD, OpenMG jukebox and the EMB Internet connection, for example.

A drawback for subscription customers is that music libraries can become completely inaccessible, including any music bought, when subscriptions end.

Some DRM history:

A different range of heavyweight media rights management products is used for business-to-business transfers (e.g. IBM EMMS).

Digital music files can be identified by serial numbers embedded in the data (watermarking) or natural patterns in the data (fingerprinting). These techniques have a number of uses:

There are even companies (Hit Song Science, Hit Predictor, etc.) who claim to rate the chart potential of songs based on digital profiles, which is of course nonsense.

Sometimes called terrestrial digital or DAB (Digital Audio Broadcasting), there are over 60 digital radio stations available in the UK. Many are the same as their analogue namesakes but some are only available to digital listeners. A special receiver is needed and the quality of the signal is good but not perfect (it is compressed and roughly equivalent to good MP3). Terrestrial digital is useful for niche programming that wouldn’t support a mass market station.

Satellite radio in the USA is mainly targeted at vehicle systems (cars and trucks). In the rest of the world it’s also used by remote and mobile listeners. This market is traditionally bigger in the USA and across Europe than the UK. The stations raise revenue through subscriptions and sales of receivers, although advertising may be necessary in the long run. The main stations (each carrying multiple channels) are:

| Satellite station | Region |

|---|---|

| Sirius XM | USA and borders |

| 1WorldSpace | South America, Europe and Asia |

Like other TV and radio, there is a general trend to integrate broadcasting with web sites (programme guides, streams, interactivity, etc.) and subscribers can listen to some services over the Internet.

Pay TV for domestic satellite and cable subscribers is controlled by encryption, special hardware and key cards. In the UK there are around 50 free digital TV and radio channels (FreeView) available to digital set-top boxes via traditional TV aerials. All the digital TV services also carry digital radio.

Internet radio is simply programmed audio streaming on the web, and the same as other kinds of modern radio. Legal stations pay (local) national publishing and phonographic licenses if they use controlled content. Stations don’t normally need a license if they play only material that isn’t assigned to royalty collection societies.

There are literally thousands of Internet stations: some on dedicated web sites; some on dedicated software players; some free; some by subscription; some on retail and magazine sites.

Internet radio is useful for niche programming that wouldn’t support a mass market station.

Several music streaming sites play music based on genre or style clues given by the listener. Two of the most popular (2006/7) are Pandora (based on the Music Genome Project) and Last.FM (based on Audioscrobbler). The music is chosen automatically from databases compiled by people or by software that monitors user’s listening habits or music collections. Because music selection is non-interactive (the user doesn’t pick the tracks) these sites use radio-style licenses.

Other indie download sites like betterPropaganda and Sputnik7’s Epitonic are adding music discovery features.